Sept. 11 united America. Twenty years later, the nation stands divided.

“The United States is a far less confident and optimistic nation now than it was in September 2001,” historian Michael J. Allen said.

By Corky Siemaszko

9/11/2021

Twenty years later, Sally Regenhard still hasn’t buried her lost New York City firefighter son, Christian.

Twenty years later, John Feal, a construction worker turned activist, still mourns the loss of that fleeting moment of national unity that arose after the twin towers of the World Trade Center fell.

Twenty years later, Army veteran Kiyoshi Mino fears the Afghans he served with, after the United States invaded the country because its Taliban government was sheltering 9/11 architect Osama bin Laden and other Al Qaeda members, will fall into Taliban hands and wonders if all that sacrifice was worth it.

And 20 years later, the ranks of the ground zero first responders who risked their lives and health to rescue those trapped in the ruins of the towers, and later retrieve the bodies of those who died there, grow smaller every year.

It was a blue-sky late summer morning when Al Qaeda terrorists in hijacked planes brought down the World Trade Center, attacked the Pentagon, crashed a plane into a field in Pennsylvania, killed more than 3,000 people, and made a mockery of America’s belief in its invincibility. And two decades later, the nation — still in the grips of the deadly Covid-19 pandemic and stunned by the chaotic end of the Afghanistan War — continues to grapple with the aftermath of that day.

“What do you write about 9/11 20 years later?” asked Feal, a demolition supervisor who lost part of a foot while toiling at ground zero and later teamed up with the comedian Jon Stewart to fight for compensation for the thousands of police officers, firefighters and others who were sickened from working on the site.

“Write that we’re deteriorating, write that more and more people who were down there are sick and dying, write that a delayed bomb filled with hate has exploded and it’s ruining our country,” he said. “All the unity on that day, after all that amazing unity on Sept. 12, 2001, when we were all Americans united together, all that unity is gone.”

Cracks in unity

Michael J. Allen, a professor of American history at Northwestern University, agreed that America is not the country it was when the twin towers fell.

“The United States is a far less confident and optimistic nation now than it was in September 2001, which marked the end of a decade of technology-fueled economic growth, foreign policy dominance and presidential centrism,” he said. “But it is also a more diverse nation with a more clear-eyed sense of the serious challenges Americans face and a more realistic sense of the dangers and limits of American power.”

How did we fall apart after the most shocking attack on the U.S. since Pearl Harbor? The first cracks in the post 9/11 unity came when the administration of then-President George W. Bush used the terrorist attacks as an excuse to attack Iraq, which had no role in them, historians said.

At the same time, millions of Muslim Americans found themselves branded terrorists by bigots and were forced to defend their religion because of bin Laden’s fanaticism.

“The Bush administration’s failed foreign policy response to the 9/11 attacks discredited the existing leadership of the Republican Party and leading Democrats like Hillary Clinton” who supported the Iraq War, Allen said.

That, he said, helped pave the way for the election of President Barack Obama, one of the few politicians who publicly opposed the Iraq War, and allowed “a new political class to emerge” before the subsequent election of his successor, Donald Trump.

“But that political class is more confrontational and enjoys less trust in a nation that has grown more divided,” Allen said. “The net effect is to leave Americans less capable of reaching consensus on any problem we face — from Covid to climate change to counterterrorism to policing — and thus unable to forge public policy responses.”

The internet also figures into the division.

“Safe to say, if what happened on Sept. 11, 2001, happened today, the response would have been vastly different,” said Syracuse University professor Robert Thompson, an expert on popular culture. “The major variable is social media and the explosion of the digital environment.”

There were conspiracy theorists who floated bogus notions that Jews were warned not to show up for work at the twin towers that day and that the attacks were an inside job or even faked, he said.

But while those notions continue to persist on the web, they did not get the sudden traction in 2001 that, for example, some of the false Covid claims that Trump promoted on Twitter did last year.

Instead, a “we’re all in this together” narrative took hold in the media in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks and remained there until the Bush administration began pushing to invade Iraq, which happened in March 2003.

“We had Jay Leno vowing not to make fun of the way President Bush mispronounces words,” Thompson said. “There is no way that warm, unified feeling would happen today.”

The endless war is over

When bin Laden masterminded the 9/11 attacks, he did so from a hideout in Afghanistan, which was then being governed by the Taliban, homegrown practitioners of an extreme version of Islam bent on returning the country to some of the practices of the Middle Ages.

The invasion Bush launched quickly dislodged the Taliban but did not destroy them. It also failed to capture bin Laden, who escaped across the border into Pakistan and continued to threaten the U.S. until he was killed in a 2011 raid ordered by Obama.

But now the Taliban are back in power, their triumphant return paved by the Trump administration’s agreement last year to pull U.S. forces out of the country, and the apparent failure of President Joe Biden’s administration to anticipate how quickly Kabul would fall.

Mino and hundreds of other Afghanistan War veterans have been frantically trying to help the Afghan interpreters who went into battle with them during America’s “longest war” escape the Taliban.

“I joined the Army right after graduating from college in July of 2001 at the age of 21, and right before 9/11,” Mino recalled. “I was in the middle of a class on dismantling and reassembling an M16 rifle in basic training when the drill sergeants announced to us that America had been attacked and that we better get ready to go to war. They were always playing mind games, so we all thought this was just another lame attempt to mess with our heads or scare us.”

Only it wasn’t. And serving as a soldier in Afghanistan and then returning to that country as a civilian aid worker, he said, he saw first-hand how America’s attempt to establish democracy was undermined by the corruption of Afghanistan’s leaders and the U.S. corporations that set up shop in the country.

“I don’t think we were in Afghanistan for a noble cause, although many of us were led to believe we were,” Mino said. “We were there to blow a lot of taxpayer money on goods and services provided by American corporations, all in the name of things like fighting terrorists, rebuilding a government, creating an Afghan National Army of course. But ultimately, the final result speaks for itself.”

The Afghan army barely put up a fight and the Taliban took Kabul without encountering any resistance.

“Our government never cared much for where that money was going or how well it was being used, and as a result the Afghan National Army was far smaller and ill-equipped than what the receipts would suggest,” Mino said.

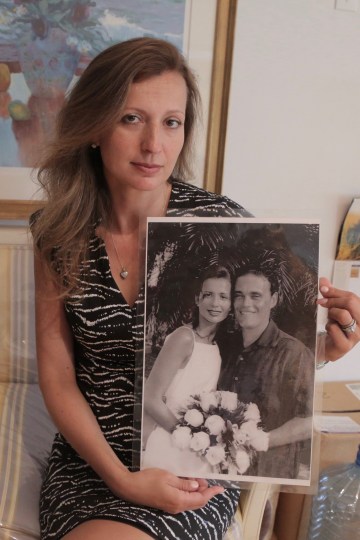

Monica Iken-Murphy, whose husband, Michael Iken, died in the south tower of the World Trade Center, bristles at critics who liken the fall of Kabul to the fall of Saigon. She said she grieves for the 13 U.S. service members who were killed by an Islamic State Khorasan group suicide bombing at the gates to Hamid Karzai International Airport and the other Americans who died fighting in Afghanistan.

“I hope our service members will not feel that their service was in vain,” she said. “We’ll be forever grateful to them for fighting for our loved ones on 9/11.”

Now a maker of podcasts, she said it was a recent conversation with former secretary of state and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton that made her reconsider America’s longest war.

“She pointed out something that we should all remember, namely that during all that time there was not another 9/11 attack on U.S. soil,” Iken-Murphy said. “And by having our forces there, the Navy SEALS were able to take out you-know-who.”

To this day, she refuses to refer to bin Laden by name.

Unidentified remains, no closure

Regenhard said “the unfinished business of 9/11 is the fact that over 1,100 people remain missing and unidentified.”

The planes that plowed into the north tower and the south tower in lower Manhattan reduced them to rubble and the remains of the scores of people who did not escape were mixed in with it.

“I have had no closure and neither have 40 percent of the families who lost their loved ones on 9/11,” she said.

What’s worse, she said, some of those still-unidentified remains are being stored in the bowels of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, the operators of which have refused repeated demands by many victims’ relatives that they be brought to the surface and placed in a “tomb of the unknown.”

“The human remains have become a lure to come into the museum and pay the $26 entrance fee,” said civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, who has been helping these 9/11 families. “It’s very distasteful.”

Museum spokesman Lee S. Cochran said 9/11 family members are never charged to visit the remains, which are in a repository that “while accessed through the museum, is not part of the museum.”

“It is a separate space operated and maintained entirely by the City of New York Office of Chief Medical Examiner,” he said in an email. “The desire to have a Tomb of the Unknown above ground has been rejected multiple times by the OCME, whose staff continues to use increasingly precise forensic analysis to try to make positive identifications and return remains to families.”

The after-effects continue to be felt by those who stepped up and helped to clear the rubble of the downed towers. More than half of the 105,000 people enrolled in the WTC Health Program have developed 9/11-related illnesses, The City news organization reported.

“I talk to dying and sick members every day, but there’s not that many left,” said Tom Frey, 56, a former New York City police detective, who was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma linked to the time he spent at the World Trade Center site and the Staten Island landfill after the 9/11 attacks, and now needs oxygen around the clock to stay alive. “It’s like we’ve been forgotten. But when the bell rang, we did what we had to do.”

But for all of those still feeling the raw wounds, there are millions of Americans alive today for whom 9/11 is something they first encountered in history books.

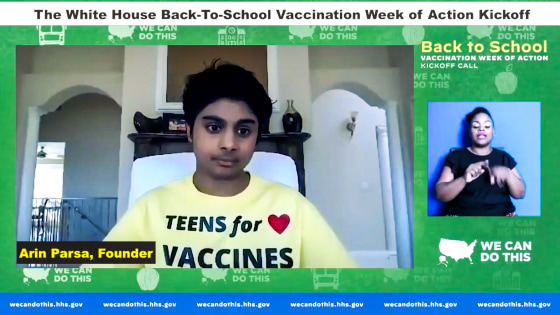

Arin Parsa, the 14-year-old founder of the Teens for Vaccines advocacy group, said his generation has no memory of Rudy Giuliani being lauded as “America’s mayor” for his leadership in New York City after the attack.

His generation can’t imagine that the U.S. Capitol — the site of the Jan. 6 riot by angry Trump supporters bent on overturning Biden’s election victory — was also where Republican and Democratic lawmakers stood together on the steps and sang “God Bless America” after 9/11, Parsa said, citing another global event that has taken precedence.

“The Covid-19 pandemic,” he said, “absolutely is and continues to be our generation’s 9/11.”