中国教育部取消286个中外合作办学机构及项目!

8/17/2021

近期,教育部的一项举措引起了热议

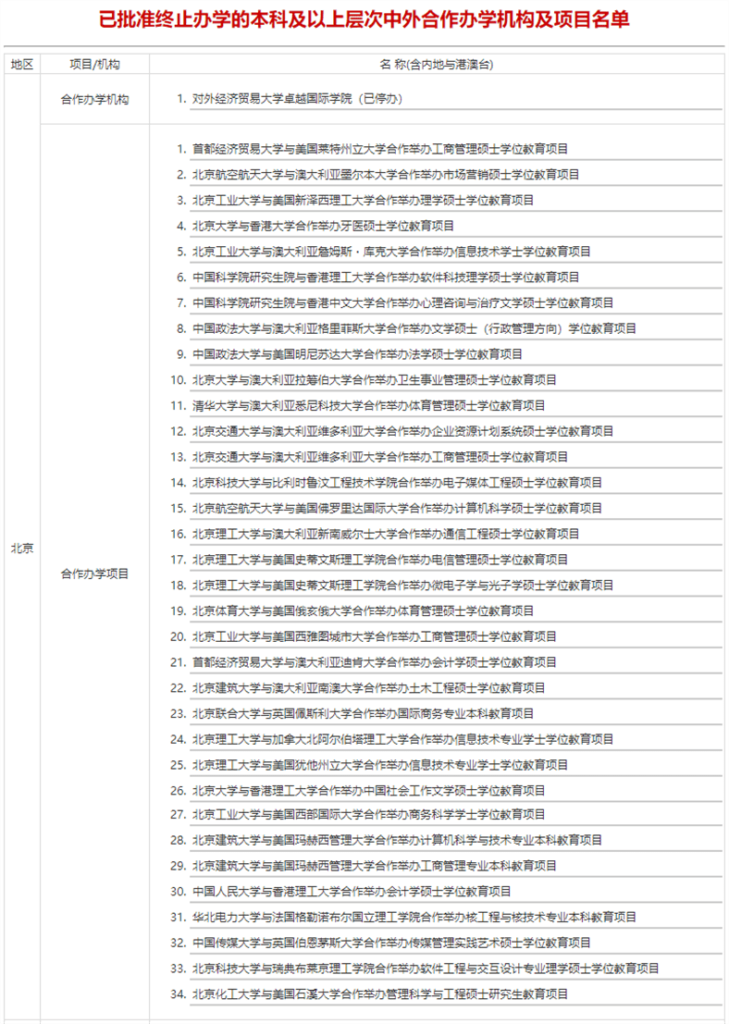

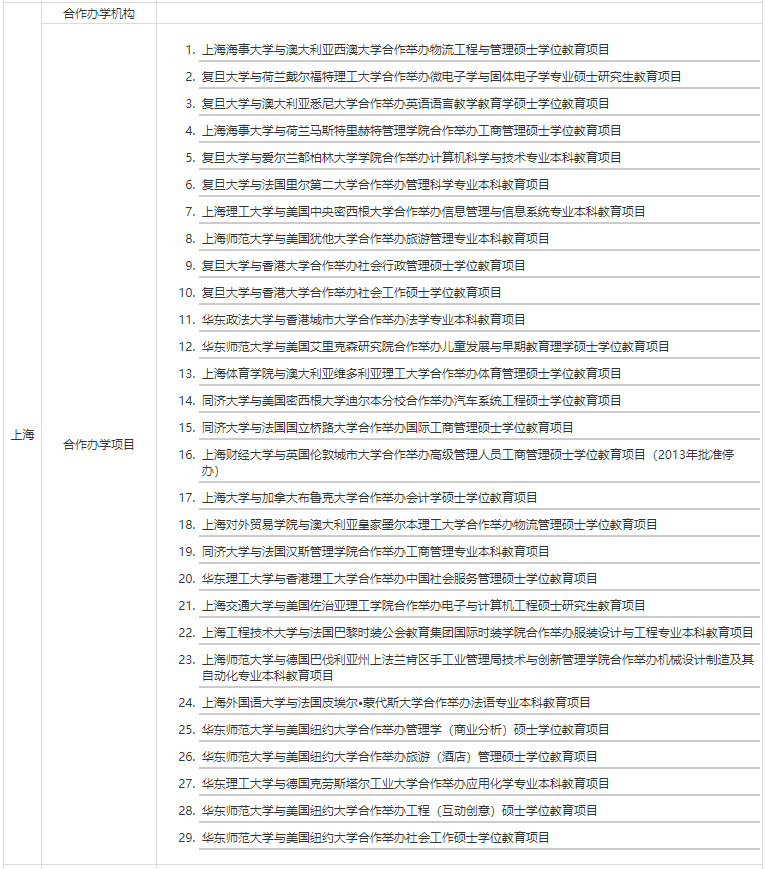

取消共286个中外合作办学机构及项目

什么是中外合作办学

如何选择中外合作办学项目

快来和凯小逸一起看看吧

286个中外合作办学机构被终止办学

去年9月,为缓解疫情影响的出国升学困境,教育部允许部分高校增加 中外合作办学机构和项目,学生毕业后可以 获得中外双方颁发的文凭。由于一年来海外疫情的不断反复,越来越多准留学家庭将目光转向了中外合作办学院校。

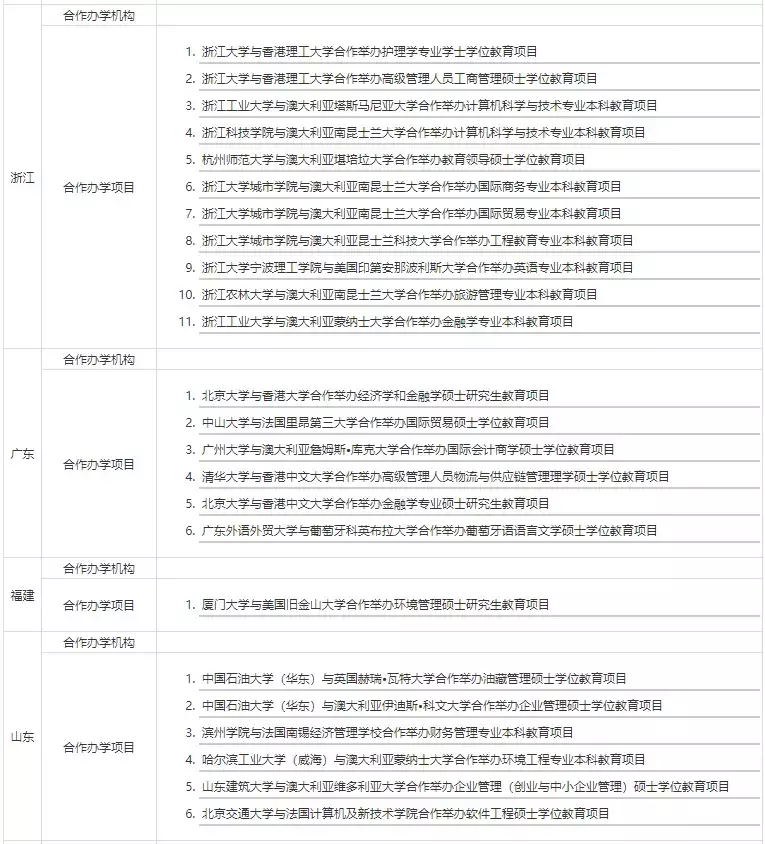

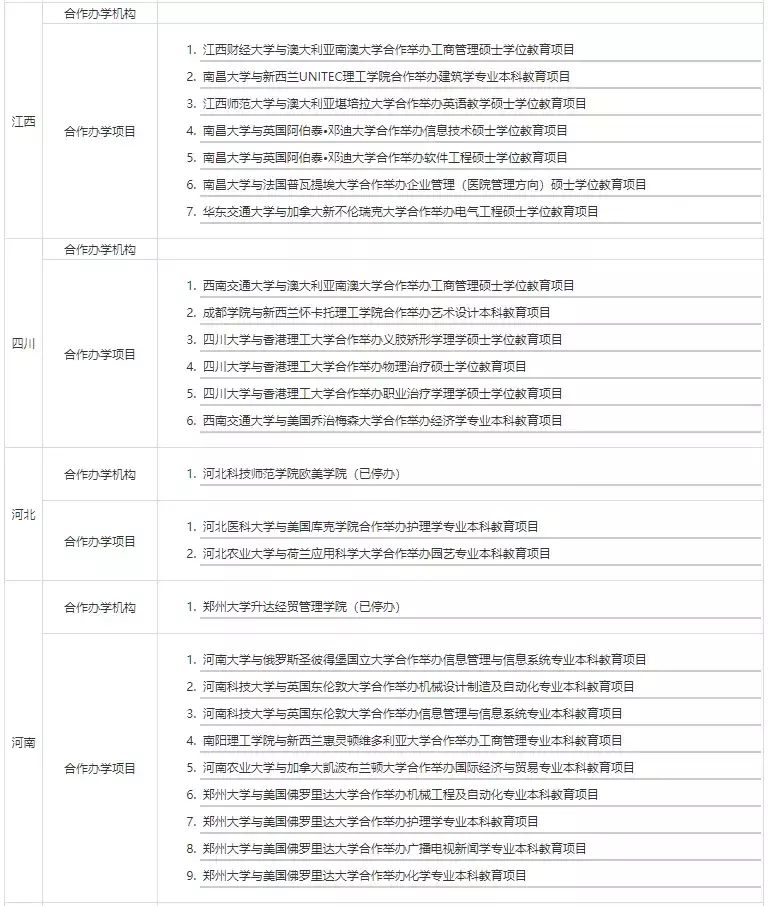

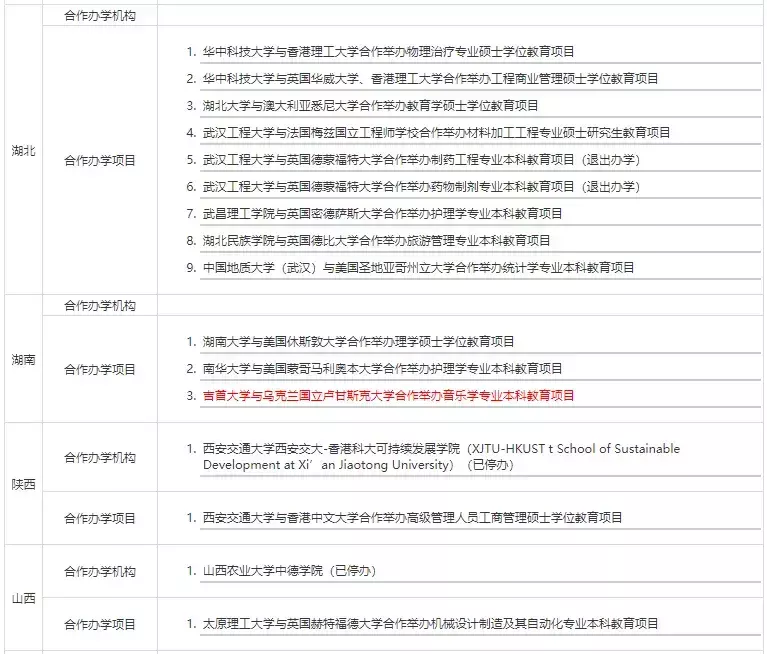

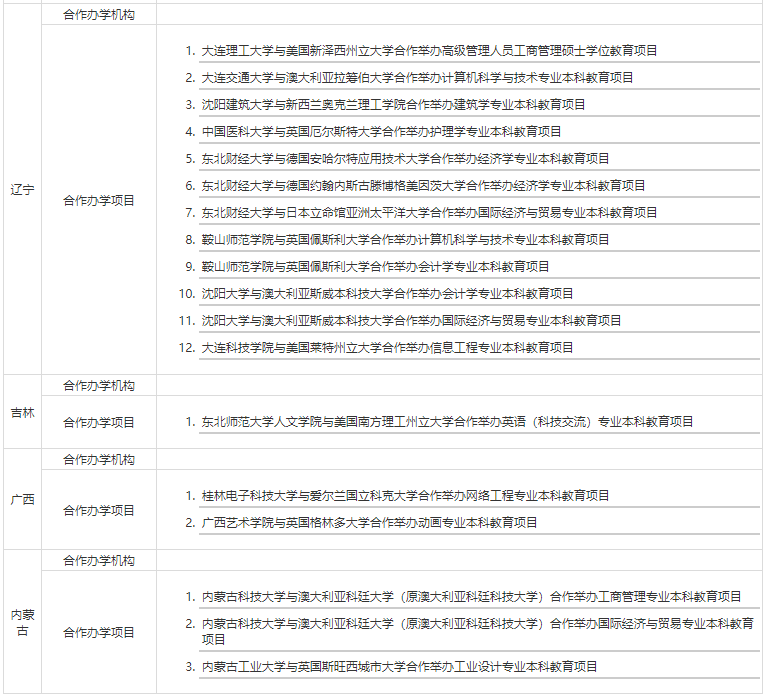

但大家在选择中外合作办学院校时也要擦亮眼睛,因为 每年都有不少中外合作办学机构、项目被终止办学的。近期,中国教育部就发布 终止 办学的本科及以上层次中外合作办学机构及项目2 86个。以下是教育部最新公布的取消中外合作办学的项目名单:

什么是中外合作办学

中外合作办学指外国法人组织、个人以及有关国际组织同中国具有法人资格的教育机构及其他社会组织,在中国境内合作举办以中国公民为主要对象的教育机构,实施教育、教学的活动。办学主体主要分为 中外合作办学机构和 中外合作办学项目两种形式。

目前, 全国具有独立法人资格的中外合作办学高校共有九所,分别为:宁波诺丁汉大学、北京师范大学—香港浸会大学联合国际学院、西交利物浦大学、上海纽约大学、昆山杜克大学、温州肯恩大学、香港中文大学(深圳)、广东以色列理工学院和深圳北理莫斯科大学。

机构和项目的区别:

性质不同

中外合作办学机构是有拥有办学、办事、办证资质以及教育部颁发给机构的教育资质及留学资质的机构,例如宁波诺丁汉大学、中国政法大学中欧法学院;而中外合作办学项目是指经国家教育部批准的国内高校与国外高校中外合作的办学项目,例如清华大学与澳大利亚麦考瑞大学合作举办应用金融硕士学位教育项目、复旦大学与挪威管理学院合作举办工商管理硕士学位教育项目等。

资质不同

中外合作办学机构有着自己的办学、办事、办证资质,有着教育部颁发给机构的教育资质及留学资质。中外合作办学项目不需要考虑资质,由其合作办学的机构提供所需资质。

管理不同

中外合作办学机构一般由机构管理,中外合作办学项目一般由高校管理,但不论是机构还是项目都由教育部门进行严格把控。

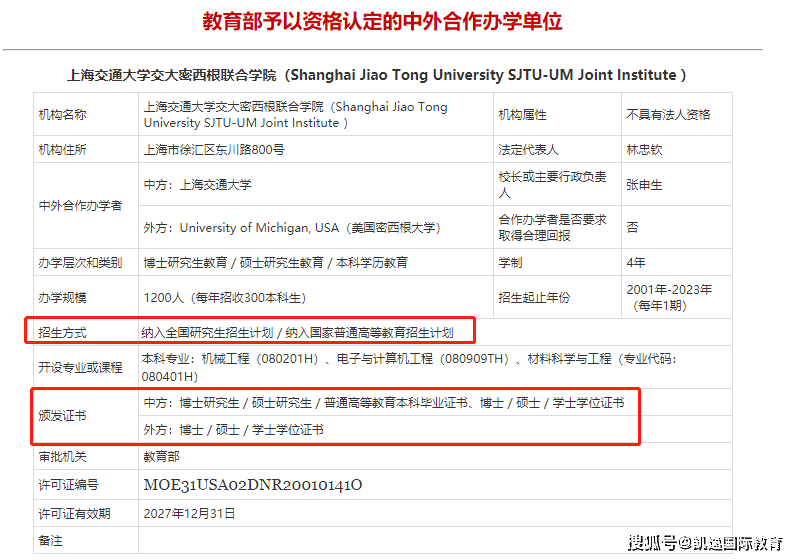

中外合作办学招生方式

根据《中华人民共和国中外合作办学条例》,实施高等学历教育的中外合作办学机构/项目招收学生纳入国家高等学校招生计划,学生必须 通过统招考试,填报志愿,毕业后分别获得中外双方学校颁发的文凭;实施非学历教育的,无须填报志愿,参加学校自己举办的入学考试即可(自主招生)。中方学校修得相应学分后,通过语言考试后再被合作学校录取,毕业后获得外方学校颁发的文凭。

就读中外合作办学需要注意什么

截至目前, 全国共有中外合作机构/项目多达1200+所。目前国内的中外合作机构/项目相对鱼龙混杂, 如何辨别优质的中外合作办学院校就读,成为困扰留学生们的问题之一。

教育部中外合作办学监管工作信息平台也发布了 《中外合作办学就读注意事项》,事项中指出,根据中外合作办学的相关情况,在就读中外合作办学时,建议特别关注和认真了解以下六个方面的情况:

一、关注所就读的中外合作办学机构或项目是否是经过合法审批。

二、关注实际办学情况,尤其是教育教学质量高低。

三、关注学校的招生宣传与实际办学情况是否一致。

四、关注招生标准。

五、关注招生计划。

六、关注中外合作办学的评估和认证情况。

如何选择中外合作办学机构/项目

在选择时一定要确定机构或项目是否是我国教育部所认可的,所颁发的证书是否是被我国所承认的。 机构/项目是否被教育部所认可,以及最新的中外合作办学信息政策、国外学历如何认证等事宜,都可通过“教育部中外合作办学监管工作信息平台”进行查询:

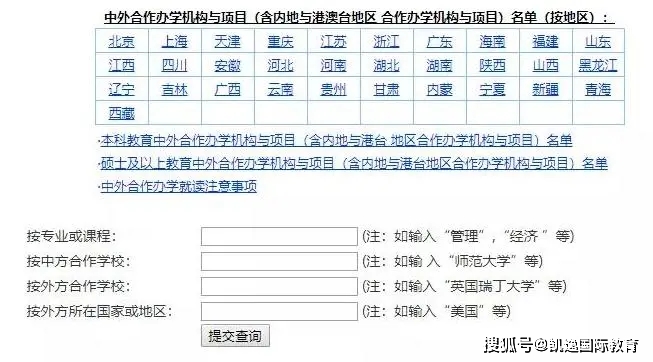

大家在选择中外合作办学机构或项目时,首先要 确认该机构或项目颁发什么证书,是中方的还是外方的,或者是中外双方的,其次一定要 核查该机构或项目是否是我国教育部认可,颁发的国外证书在我国是否同样被承认。具体查询方式如下:

1.进入教育部中外合作办学监管工作信息平台查询中外合作办学机构及项目名单。

2. 按地区查找,或输入想要查询的机构、或项目的信息进行查找,如果可以找到说明是被教育部认可的。

3. 点击项目或机构,可查看相关信息。

要特别注意的是招生方式与颁发证书,在这两处可以看出该项目是计划内还是计划外,以及最后能拿到什么证书。

US must outcompete China for a stable relationship: Daniel Russel

Beijing’s aggression comes from perception that America is declining, former official says

TSUYOSHI NAGASAWA, Nikkei staff writer

7/10/2021

WASHINGTON — The secret visit of U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Beijing on July 9-11, 1971, kicked off an American policy of engagement with China. Fifty years later, with China on track to overtake the U.S. economy as early as 2028, bilateral relations are at a crossroad.

In an interview with Nikkei, Daniel Russel, former U.S. assistant secretary of state for East Asia and Pacific affairs during the Obama administration, said the nature of the relationship is changing, and it would be wrong to assume that Washington would return to the “good old days,” supporting China’s growth while making an effort to avoid friction and confrontation.

But Russel, now vice president for international security and diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute, also stressed that aiming for regime change in Beijing is unrealistic and unwise, and would be in line with the “catastrophic” failures of attempted regime changes in the Middle East.

Edited excerpts from the interview follow:

Q: Since Kissinger began an engagement policy with China in the 1970s, the U.S.-China relationship has been relatively stable. The U.S. has invited China into the international system. Looking back, how do you evaluate the pros and cons of this policy?

A: If we took a step back and looked broadly at the historical record, we see that the United States deliberately chose a policy of engaging China and supporting its development, first back in 1972 under President Richard Nixon, where this was part of the strategy for containment of the Soviet Union, but then again in the ’90s, when Bill Clinton was president, after the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union. There was a second policy of engaging China that led up to the entry of China into the WTO.

From the Clinton era on, America’s policy toward China was based on the view that a stable China, a prospering China, would serve the best interests of the United States, in part because a weak China, or an insecure China, would likely pose a lot of risks to U.S. interests and to our allies.

I’ve never heard a persuasive argument that it would have been better to do something different than engagement, at those junctures. The United States made a common-sense decision, to try to engage China and to shape its behavior, to integrate China and to give it a stake in the international system, that the United States had largely designed.

And, while people hoped for political liberalization, I don’t think that political liberalization was the reason that the U.S. government and other governments took this approach, because what was the alternative?

Who is going to argue that an effort to isolate China and to contain China, or to destabilize China would have been a better strategy? It would have been a recipe for disaster.

Today, there is a kind of new conventional wisdom that is based on the view that cooperation with China is impossible, that engagement with China is a failure.

If you look at the historical record, that’s just not defensible, that’s not true.

But that doesn’t mean that we can go back to the “good old days” where we tried to support China’s growth, where we made an effort to avoid friction and confrontation.

There are two reasons for this.

In the past, as long as there was a large disparity, a gap, in military power and economic power between the two countries, the relationship was reasonably stable. But China has become much more economically successful and much more militarily and technologically capable. China is now close to being a peer power to the United States, which it never was.

Secondly, in the Xi Jinping era — which now is about almost nine years — China’s leadership has become more assertive, more ideological, and more brazen, more overt, in challenging global norms and challenging U.S. leadership. We’ve seen bullying behavior intensify by China.

Q: What were negotiations with China like in the years of President Barack Obama?

A: We had two very different experiences with the Chinese. On the South China Sea, Obama had very direct, very blunt, discussions with Chinese President Xi Jinping repeatedly, from 2013 and the Sunnylands meeting on, each time more forcefully warned Xi that China’s island building, its reclamation, its activities, were creating risk, and that the United States had a responsibility to the defense of the Philippines and more broadly had a strong commitment to freedom of navigation, and could not accept efforts by China to claim the so-called nine-dashed line, or to develop outposts in international waters, and that this was damaging the U.S.-China relationship.

Finally, in the meeting in 2015, Xi made an assurance, and he made a public assurance as well, that China would not militarize the outposts that it built.

But, in that case, China did not ultimately honor that commitment, and the problematic behavior continued. And it had a very damaging effect on U.S. relations with China.

The issue of cyber theft, and particularly the Chinese government’s sponsorship of cyber-enabled theft of American intellectual property from companies, that was a different experience, because for years Obama raised this issue with Xi and warned of consequences, and told Xi that, although China was denying it, the United States knew that China was conducting these attacks, and that they couldn’t hide from us.

And finally, the Chinese saw evidence that the United States was preparing to take very severe action in retaliation for this, and the Chinese leadership recognized that they were reaching a dangerous, critical point, and so they sent to Washington the top security official in China, Meng Jianzhu, who came with instructions: don’t come home without an agreement.

And he stayed in Washington for several days. He met with the U.S. government team. And you may remember that the U.S. and China issued a four-point agreement. In that agreement, China essentially acknowledged that this cyber theft had occurred, committed to end it, and made some public commitments that they did implement, they did honor.

For several years after that, the U.S. agencies that were monitoring cyberattacks formed a judgment that China had, in fact, scaled back significantly the attacks that at least the government, the state, was supporting.

Q: Based on those lessons, how should the U.S. approach China?

A: My judgment is that Chinese behavior has become much more troubling and dangerous as Chinese leaders have begun to believe that they are as strong as the United States, that they are getting stronger and the U.S. is getting weaker.

I don’t think that it is wise or feasible to pursue a strategy of weakening China. Instead, it is necessary and wise to pursue a strategy of strengthening the United States and its allies because, as I pointed out before, when the power differential between the United States and China was wider, the relationship was very stable.

As long as the Chinese perception is that the United States is weak, is on the decline, is withdrawing from its traditional role in shaping and often leading international affairs, in rules-setting and so on, and has abandoned the sort of moral high ground that gave the United States so much soft power over the decades, China is incentivized to challenge more directly.

If and when the Chinese leaders see more evidence that the United States is demonstrating resilience, is renewing and reinventing itself, that the overall strength of the democratic communities is growing, not shrinking, the Chinese leaders will be much more open to compromise. They will be much more flexible, much more careful, in their behavior.

Chinese leaders are Leninists and Leninists respect strength and have contempt for weakness.

If the United States, over the course of this year, shows, for example, extraordinary ability to stop the spread of COVID-19, an extraordinary ability to develop vaccines that have 96% to 97% effective rates, demonstrates the ability to manufacture billions of doses and make them available to countries around the world, whereas China, despite its very strict and draconian controls, now continues to battle emerging cases of the delta variant, and the Chinese vaccine, Sinovac, which they have distributed around the world, is now revealed to be far less effective in preventing COVID than advertised, that’s a way in which the United States is already demonstrating its strength.

It is already outcompeting. We’re not hurting China. We’re not blocking China. But we are outperforming China.

Q: You talked about the leadership of Xi Jinping himself. How is he different from former presidents Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin before him?

A: Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao were not democrats; they had no interest in sharing power. But they were also pragmatists, and they were continuing the tradition of Deng Xiaoping, the tradition of “hiding and biding,” the tradition of opening and reform.

Xi Jinping represents a more nationalist and a more ideological strain of Leninism. In the Chinese communist system, he is clearly representing those who believe that more control is the right answer, and that political liberalization is a recipe for disaster that China cannot afford.

Q: China hawks in the U.S. have argued that the biggest problem is the Chinese Communist Party and thus the U.S. should seek regime change.

A: Number one, the people who are advocating regime change are the very people that have experimented with regime change in Iraq, in Libya, and other parts of the world. And, in every case, it has been a catastrophic failure. It’s not only that it didn’t succeed; it’s that it created immense problems in the country and immense problems in the United States.

The United States does not have the power to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party, and we know from experience that, even if we were successful, the consequences are unpredictable and immensely dangerous.

We can certainly hope for a change and an improvement. There’s much that we can do to bolster civil society within China, and much we can do to help strengthen institutions other than the Chinese Communist Party, in China.

There is a lot of pressure that can be applied externally on the Chinese leadership to limit their behavior. But the notion of the United States reaching in and changing the government in China is unrealistic and unwise.

Q: Is there a similarity between the current situation and the 1970s, in the sense that the Biden administration is now seeking a stable and predictable relationship with Russia so as to focus more on China and try to drive a wedge between China and Russia?

A: The big difference in the 1970s was that Moscow and Beijing were in an intense rivalry and were virtual enemies. Another difference was that the U.S. and the Soviet Union were in a very significant Cold War, in which we had very little economic or other mutual dependencies and were largely separated into independent blocs, and we were competing around the world for influence, in a very direct way.

Today, Russia is a relatively weak power that is largely focused on making problems, making mischief for the U.S. and for the West.

And the relationship between Moscow and Beijing is very cooperative, very collaborative. And unlike the Soviet Union, China is well integrated into the global system, the multilateral system, and the degree of economic and technological integration between China, the United States, and the rest of the West, is unimaginably large.

So, I think, in those respects, we’re in a very, very different world. And, while it is problematic for the United States when China and Russia cooperate in causing problems for us and our friends, and while there would be some virtue and value in trying to provide incentives for Moscow to moderate its behavior and to refrain from that kind of mischief-making, I don’t think there is any prospect for a kind of fundamental alteration of the triangular relationship, the way that Kissinger and Nixon changed it in 1972.

China beating US by being more like America

Cultivating human capital will be essential if the US rather than China is to be the base of the next industrial revolution

By BRANDON J WEICHERT

4/25/2021

The United States transitioned from an agrarian backwater into an industrialized superstate in a rapid timeframe. One of the most decisive men in America’s industrialization was Samuel Slater.

As a young man, Slater worked in Britain’s advanced textile mills. He chafed under Britain’s rigid class system, believing he was being held back. So he moved to Rhode Island.

Once in America, Slater built the country’s first factory based entirely on that which he had learned from working in England’s textile mills – violating a British law that forbade its citizens from proliferating advanced British textile production to other countries.

Samuel Slater is still revered in the United States as the “Father of the American Factory System.” In Britain, if he is remembered at all, he is known by the epithet of “Slater the Traitor.”

After all, Samuel Slater engaged in what might today be referred to as “industrial espionage.” Without Slater, the United States would likely not have risen to become the industrial challenger to British imperial might that it did in the 19th century. Even if America had evolved to challenge British power without Slater’s help, it is likely the process would have taken longer than it actually did.

Many British leaders at the time likely dismissed Slater’s actions as little more than a nuisance. The Americans had not achieved anything unique. They were merely imitating their far more innovative cousins in Britain.

As the works of Oded Shenkar have proved, however, if given enough time, annoying imitators can become dynamic innovators. The British learned this lesson the hard way. America today appears intent on learning a similar hard truth … this time from China.

By the mid-20th century, the latent industrial power of the United States had been unleashed as the European empires, and eventually the British-led world order, collapsed under their own weight. America had built out its own industrial base and was waiting in the geopolitical wings to replace British power – which, of course, it did.

Few today think of Britain as anything more than a middle power in the US-dominated world order. This came about only because of the careful industrial and manipulative trade practices of American statesmen throughout the 19th and first half of the 20th century employed against British power.

The People’s Republic of China, like the United States of yesteryear with the British Empire, enjoys a strong trading relationship with the dominant power of the day. China has also free-ridden on the security guarantees of the dominant power, the United States.

The Americans are exhausting themselves while China grows stronger. Like the US in the previous century, inevitably, China will displace the dominant power through simple attrition in the non-military realm.

Many Americans reading this might be shocked to learn that China is not just the land of sweatshops and cheap knockoffs – any more than the United States of previous centuries was only the home of chattel slavery and King Cotton. China, like America, is a dynamic nation of economic activity and technological progress.

While the Chinese do imitate their innovative American competitors, China does this not because the country is incapable of innovating on its own. It’s just easier to imitate effective ideas produced by America, lowering China’s research and development costs. Plus, China’s industrial capacity allows the country to produce more goods than America – just as America had done to Britain

Once China quickly acquires advanced technology, capabilities, and capital from the West, Chinese firms then spin off those imitations and begin innovating. This is why China is challenging the West in quantum computing technology, biotech, space technologies, nanotechnology, 5G, artificial intelligence, and an assortment of other advanced technologies that constitute the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Why reinvent the wheel when you can focus on making cheaper cars and better roads?

Since China opened itself up to the United States in the 1970s, American versions of Samuel Slater have flocked to China, taking with them the innovations, industries, and job offerings that would have gone to Americans had Washington never embraced Beijing.

America must simply make itself more attractive than China is to talent and capital. It must create a regulatory and tax system that is more competitive than China’s. Then Washington must seriously invest in federal R&D programs as well as dynamic infrastructure to support those programs.

As one chief executive of a Fortune 500 company told me in 2018, “If we don’t do business in China, our competitors will.”

Meanwhile, Americans must look at effective education as a national-security imperative. If we are living in a global, knowledge-based economy, then it stands to reason Americans will need greater knowledge to thrive. Therefore, cultivating human capital will be essential if America rather than China is to be the base of the next industrial revolution.

Besides, smart bombs are useless without smart people.

These are all things that the United States understood in centuries past. America bested the British Empire and replaced it as the world hegemon using these strategies. When the Soviet Union challenged America’s dominance, the US replicated the successful strategies it had used against Britain’s empire.

Self-reliance and individual innovativeness coupled with public- and private-sector cooperation catapulted the Americans ahead of their rivals. It’s why Samuel Slater fled to the nascent United States rather than staying in England.

America is losing the great competition for the 21st century because it has suffered historical amnesia. Its leaders, Democrats and Republicans alike, as well as its corporate tycoons and its people must recover the lost memory – before China cements its position as the world’s hegemon.

The greatest tragedy of all is that America has all of the tools it needs to succeed. All it needs to do is be more like it used to be in the past. To do that, competent and inspiring leadership is required. And that may prove to be the most destructive thing for America in the competition to win the 21st century.

Source: https://asiatimes.com/2021/04/china-beating-us-by-being-more-like-america/

Feb 18, 2021

Aug 4, 2020