网友分享: 美帝国英帝国苏联和大清结构类似

9/18/2021

都有核心区,属国,势力范围 。

国家通过财政支持庞大帝国的军事开支,控制边疆地区 。

一旦财政破产,边疆就控制不住了 。

英国财政破产之后,把所有殖民地都吐了出来 。

苏联财政崩溃之后,养不起加盟共和国,也不能给东欧国家补贴,所以都拜拜了 。

美国也在重蹈覆辙,自己没钱了,原来是倒贴钱补贴小国跟着自己,让出市场养肥了东亚四小龙,现在也养不起了,还要敲日本韩国竹杠,给法国拆台。没钱了之后会众叛亲离。

最后,美国要是能守住国家不分裂就烧高香了。

古往今来,大帝国完蛋没有不分裂的 。

Comparing the rise and fall of empires

9/18/2021

Overview

- An empire consists of a central state that also controls large amounts of territory and often diverse populations

- Empires rise and grow as they expand power and influence, and can fall if they lose control of too much territory or are overthrown

- Historians can better understand these processes by comparing how they occurred in different empires

What is an empire?

By now, you have learned about several major empires. Just to review, the term empire refers to a central state that exercises political control over a large amount of territory containing many diverse groups. Often, this centralized power rules from one or several capital cities. We usually refer to an empire as if it were a single unit. But, because empires are so large, they are often divided into smaller, more manageable political units, usually called provinces.

Comparing how empires rise and grow

For an empire to grow, one state has to take control of other states or groups of people. To better understand these processes, historians can compare specific empires against one another.

By comparing different empires, historians see that the process of growth had some similarities and some differences across empires. The Achaemenid Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great grew substantially in less than 30 years and reached its greatest extent within 75 years. The Roman Republic was founded in the sixth century BCE, but the Roman Empire didn’t reach its greatest extent until 117 CE.

Empires grow for different reasons. The Persian Empire of the Achaemenids was built largely through military conquest. The Maurya Empire in India used a combination of political sabotage, religious conversion, and military conquest to expand its rule. The Romans, although a militaristic society, did not generally set out to conquer territory. But, they did get involved in many wars. After defeating enemies, Rome usually offered them some level of citizenship in exchange for loyalty.

The main point is that imperial growth is about a central state extending political control over territory and people. This can be achieved by military, economic, or cultural means—usually a combination of these factors!

Rapid expansion—the rise of Alexander the Great

Alexander of Macedon is remembered as one of the great empire builders of history. But how much of his success was due to his personal qualities? The rapid rise of Alexander’s empire was an example of the process by which a small state can grow into a huge empire. It also demonstrated how events and circumstances beyond the central state play a role in the state’s success in building an empire.

Although he is often remembered for being the father of Alexander the Great, Philip II of Macedon—who reigned from 359 BCE to 336 BCE—was an accomplished king and military commander in his own right. He set the stage for his Alexander’s victories over Persia. Philip II used bribery, warfare, and threats to secure his kingdom, and without his insight and determination, history might never have heard of Alexander.

In 336 BCE, after Philip was killed, Alexander embarked on the great campaign his father had been planning: the conquest of the mighty Persian Empire. Alexander had impressive military leadership abilities, but he was also aided by political instability in Persia. Alexander’s victories convinced many local rulers to swap Persian imperial control for Alexander’s rule. Alexander did not drastically challenge existing administrative systems, rather, he adapted them for his purposes. By 327 BCE, the Persian Empire was firmly under his control.

Alexander’s conquest of Persia can be viewed as a change in leadership, as well as an act of territorial expansion. The territory that constituted the Persian Empire remained largely intact under Alexander’s rule. Several factors, including the existing conditions in the Persian Empire and the imperial foundations laid by his father, combined with Alexander’s military skill to make his imperial adventure successful.

Internal reform—the rise of Han China

The Qin dynasty was short-lived—from 221 BCE to 206 BCE. But during its brief existence, it laid the groundwork for an extensive imperial bureaucracy that would expand and reform under the Han Dynasty that followed it. Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of the Qin, consolidated land and power during his conquests that ended the Warring States Period. Under Qin Shi Huang, all power came directly from the Emperor.

The first Emperor of the Han, Han Gaozu, retained much of the Qin imperial bureaucracy but reduced the harshness of edicts and taxes. Confucianism had been suppressed by the Qin. Han Gaozu openly promoted Confucianism as the state ideology, encouraging moral uprightness and virtue, rather than governing solely through fear and oppression.

Further, the Han leaders pressed a policy of cultural conversion on newly-conquered regions. Through efforts to teach Confucian ethics, the Han emperors built a shared sense of identity among their diverse subjects. Allegiance to the central Han state became more than a political or economic relationship—it was part of a cultural identity.

Comparing how empires fall

When historians say that an empire fell, they mean that the central state no longer exercised its broad power. This happened either because the state itself ceased to exist or because the state’s power was reduced as parts of the empire became independent of its control. Because empires are large and complex, when historians talk about the fall of an empire, they are typically talking about a long process rather than a single cause!

Some of the broad factors that historians use to help explain imperial collapse are:

- Economic issues

- Social and cultural issues

- Environmental issues

- Political issues

These are not causes by themselves, but ways to categorize causes. For example, you wouldn’t say, “Politics are one reason Rome fell.” You would look at specific political factors, such as the impact of civil wars. Although these categories of factors are necessary if we want to talk about imperial collapse, there is not a single explanation for why empires fall!

Rapid collapse—Achaemenid Persia

Although there had been internal conflicts in Achaemenid Persia prior to Alexander’s invasion, the empire remained largely intact for much of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. However, the existence of internal divisions made Persia vulnerable to invaders hoping to strip Persia of territory.

In 334 BCE, Alexander of Macedon invaded the Persian Empire, and by 330 BCE, the Persian king, Darius III, was dead—murdered by one of his generals. Alexander claimed the Persian throne and left the officials and institutions of the cities he captured in place to manage his massive empire. In this sense, Alexander could be viewed as simply stepping into the role of Persian emperor. Rather than destroying the central Persian state, Alexander took over as its new ruler.

When Alexander died without an heir in 323 BCE, his generals divided the empire among themselves. It was at this point that the central state of Persia collapsed and was replaced by multiple competing states. This division occurred within a matter of years.

So, the factors that contributed to the fall of Achaemenid Persia were largely political and military. Political divisions made the empire weaker militarily.

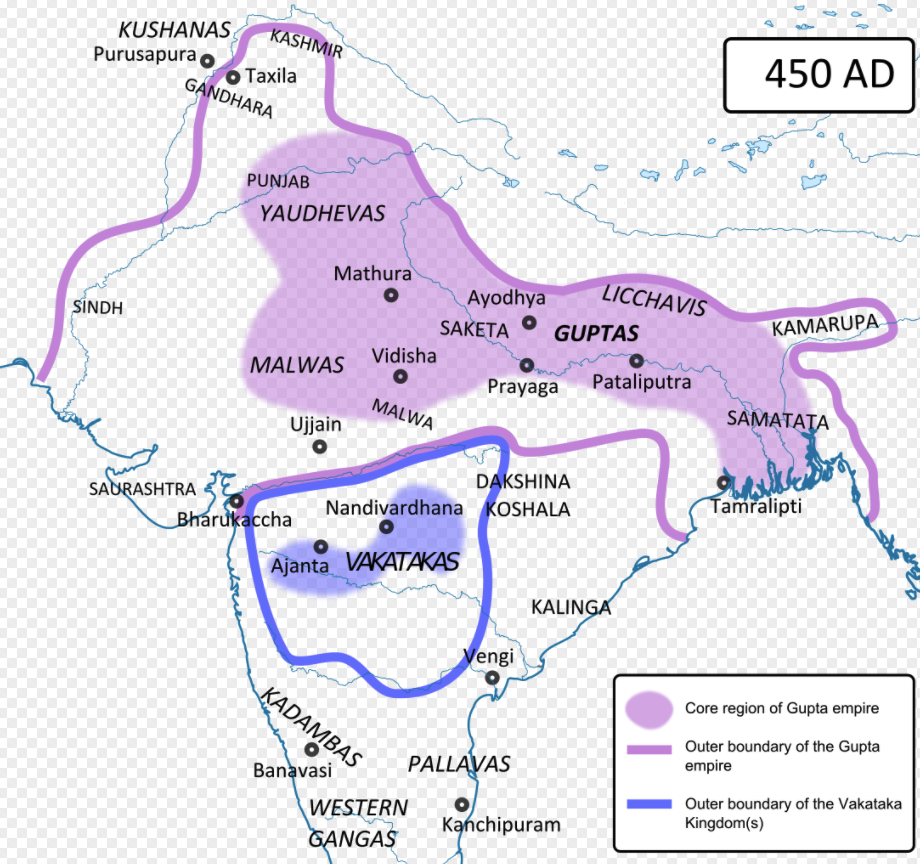

Slow death of an empire—the Guptas

The Gupta dynasty ruled a large empire in northern India from roughly 320 CE to 550 CE. This dynasty reached the height of its power in about 450 CE, as shown on the map below. From about 450 CE on, the Gupta empire faced invasions in the northwest region of the empire from the Hephthalites—sometimes called the White Huns. These ongoing attacks drained Gupta military and financial resources and led to century-long process of decline.

Continued conflict with the White Huns saw the Gupta Empire lose much of its northwest territory by about 500 CE. The Gupta Empire was able to force the Huns out in 528 CE. However, the economic impact of the loss of territory and continued fighting left the Gupta dynasty weak and poor. Over the next several decades, various regions broke away from Gupta control, and neighboring states—like the Vakataka Kingdom and Malwa—grew more powerful.

By 550 CE, the Gupta empire no longer existed. However, a small Gupta kingdom continued to exist for another century or so. The Gupta Empire is an example of imperial collapse where the central state continues to exist, but is unable to exert its power and influence beyond a limited territory. This can be contrasted with the Western Roman Empire, whose last emperor was forced out of power, eliminating the central Roman state.

The factors that contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire were largely military and economic. The economic issues were a result of the military challenges the empire faced. This is turn led to political issues as the government lost territory and was weakened.

Big takeaways

- Empires rise and fall for many different reasons

- Historians often categorize these reasons as political, economic, social and cultural, or environmental

- Comparing the specific causes and effects of the rise and fall of different empires can help us better understand the concept of empires across different times and locations

美媒文章:阿富汗布局失败、中俄崛起,“美利坚帝国”已衰落

环球网

9/09/2021

9月6日,《纽约时报》发表专栏作家罗斯·杜塔(Ross Douthat)的文章,他在文中表示,美国在伊拉克的困局和阿富汗的失败,以及俄罗斯的复仇主义和日益增长的中国力量,都削弱了“美利坚帝国”的发展,美国在“9·11”事件后谋求真正统治全球的幻想已经破灭。

杜塔认为,世界上存在“三个美利坚帝国,而不是一个”。他解释称:“首先是中央帝国,即美国大陆以及周边太平洋和加勒比地区的属地;然后是外展帝国,由美国人在二战后占领和重建并置于我们的军事保护伞下的地区组成:基本上是西欧和环太平洋地区;最后,还有美国的世界帝国,在精神上,它存在于美国的商业和文化力量所及之处,在现实中,它存在于美国的附庸国和军事设施的组合中。”

杜塔宣称,“在某种程度上,第三个帝国是我们(美国)最了不起的成就”,但它面积太大,因此很难整合,也很难施加直接的控制。

杜塔写道,“帝国时代最明显的美国失败”从1960年代的东南亚开始,然后是9·11之后的中东和中亚。他认为,这些失败“都是源于我们的傲慢想法,我们认为能把世界帝国作为外展帝国的一个简单的延伸,普遍使用北约那样的协定,并将二战后日本和德国的模式应用于越南、伊拉克或阿富汗。”

杜塔特别指出:“在我们最近将潜在竞争对手美国化的努力中,我们经历了类似的失败,虽然没有那么多流血事件,但战略后果更为严重。”他表示,美国曾在1990年代设想把自己与俄罗斯的关系发展成为类似与德国或日本的那种关系,而俄罗斯出现了“普京主义”;美国在过去20年里对中国施加影响,而中国坚持独立发展,成为了“一个真正的对手”。

杜塔在文中称,虽然美利坚“世界帝国”的失败不会动摇美利坚“中央帝国”,但会带来一定影响。虽然美国不会被塔利班推翻,但在美利坚“外展帝国”,在西欧和东亚,美国给人留下的虚弱形象会加速事态发展,真正威胁到“美国体系”。而在美利坚“中央帝国”,加速衰落的感觉将渗透到国内的所有争论中,扩大已经存在的意识形态分歧,鼓励分裂和导致迫在眉睫的内战。

作者最后写道,读者可能认为不如干脆摆脱掉什么“美利坚帝国”,但是让美国变回一个普通国家,“很难不经历一次痛苦的坠落”。

Ross Douthat: The American empire in retreat

By ROSS DOUTHAT

9/09/2021

In one of the more arresting videos that circulated after the fall of Kabul, a journalist follows a collection of Taliban fighters into a hangar containing abandoned, disabled U.S. helicopters. Except that the fighters don’t look like our idea of the Taliban: In their gear and guns and helmets (presumably pilfered), they look exactly like the American soldiers their long insurgency defeated.

As someone swiftly pointed out on Twitter, the hangar scene had a strong end-of-the-Roman Empire vibe, with the Taliban fighters standing for the Visigoths or Vandals who adopted bits and pieces of Roman culture even as they overthrew the empire. For a moment, it offered a glimpse of what a world after the American imperium might look like: Not the disappearance of all our pomps and works, any more than Roman culture suddenly disappeared in 476 A.D., but a world of people confusedly playacting American-ness in the ruins of our major exports, the military base and the shopping mall.

But the glimpse provided in the video isn’t necessarily a foretaste of true imperial collapse. In other ways, our failure in Afghanistan more closely resembles Roman failures that took place far from Rome itself — the defeats that Roman generals suffered in the Mesopotamian deserts or the German forests, when the empire’s reach outstripped its grasp.

Or at least that’s how I suspect it will be seen in the cold light of hindsight, when some future Edward Gibbon sets out to tell the story of the American imperium in full.

That cold-eyed view, taken from somewhere centuries hence, might describe three American empires, not just one. First there is the inner empire, the continental USA with its Pacific and Caribbean satellites.

Then there is the outer empire, consisting of the regions that Americans occupied and rebuilt after World War II and placed under our military umbrella: basically, Western Europe and the Pacific Rim.

Finally, there is the American world empire, which exists spiritually wherever our commercial and cultural power reaches, and more practically in our patchwork of client states and military installations. In a way, this third empire is our most remarkable achievement. But its vastness inevitably resists a fuller integration, a more direct kind of American control.

Seen from this perspective, the clearest American defeats of our imperial era, first in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and then in the Middle East and Central Asia after 9/11, have followed from the hubristic idea that we could make the world empire a simple extension of the outer empire, making NATO-style arrangements universal and applying the model of post-World War II Japan and Germany to South Vietnam or Iraq or the Hindu Kush.

We have experienced similar failures, with less bloodshed but more significant strategic consequences, in our recent efforts to Americanize potential rivals.

Our disastrous development efforts in Russia in the 1990s led to a Putinist reaction, not the German- or Japanese-style relationship we had imagined. The unwise “Chimerican” special relationship of the past two decades seems to have only smoothed China’s path to becoming a true rival, not a junior partner in a peaceful world order.

Both kinds of failures and their consequences — Russian revanchism and growing Chinese power combined with quagmire in Iraq and defeat in Afghanistan — have meaningfully weakened the American world empire, and extinguished our post-9/11 fantasy of truly dominating the globe.

But so long as we have the other two empires to fall back on, from our cold-eyed Gibbonian perspective the situation still looks more like a scenario where Rome lost frontier wars to Parthia and Germanic tribes simultaneously — a bad but recoverable situation — than like outright imperial collapse.

That said, defeats on distant frontiers can also have consequences closer to the imperial core. The American imperium can’t be toppled by the Taliban. But in our outer empire, in Western Europe and East Asia, perceived U.S. weakness could accelerate developments that genuinely do threaten the American system as it has existed since 1945 — from German-Russian entente to Japanese rearmament to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

Inevitably those developments would affect the inner empire, too, where a sense of accelerating imperial decline would bleed into all our domestic arguments, widen our already yawning ideological divides, encourage the feeling of crackup and looming civil war.

Which is why you can think, as I do, that it’s a good thing that we finally ended our futile engagement in Afghanistan and still fear some of the possible consequences of the weakness and incompetence exposed in that retreat.

And applied to the American empire as a whole, this fear points to a hard truth: You might think that our country would be better off without an imperium entirely, but there are very few paths back from empire, back to just being an ordinary nation, that don’t involve a truly wrenching fall.

Ross Douthat is a columnist for The New York Times.