路透:台湾芯片产业成美中交锋前线

中央社 | 台中

12/27/2021

路透社今天再推题为「台湾芯片产业已成为美中交锋前线」的台湾专题,文中提及在美中两大超级强权对决之际,台湾靠半导体业塑造出自身的防御绝招,已变得美中双方都不可或缺。

路透社指出,台湾芯片业巨擘台积电主宰最先进半导体制造,掌握对于当今和未来尖端数字设备和武器皆至关重要的技术。根据业界估计,台积电占了这类芯片全球产量的90%以上。

美中两大超强如今都发现,自己深深依赖台湾这个小岛国,在两国日益紧张的竞争中,台湾身处中心位置。

路透社分析,对于华府而言,若让日益强大的中国在冲突中占据台积电的晶圆厂,将威胁到美国的军事和科技领导地位。

然而,若北京当局进行侵略,并无法保证可以完好无损地夺取这些珍贵的晶圆厂。这些工厂可能轻易沦为战斗中的牺牲品,切断对中国广大电子产业的芯片供应。

即便它们在中国接管下幸存,也几乎笃定会在全球供应链中遭到切断。

路透社提及,美中双方都想打破对台积电的依赖。华府已说服台积电在美国设立制造先进半导体的晶圆厂,并准备花费数百亿美元重建国内芯片制造产业。

另一方面,北京当局也为此砸下巨资,但中国芯片产业在多项关键领域落后台湾10年左右。分析师并认为,预计未来几年双方差距将会扩大。

这些芯片代工厂对全球经济如此宝贵,以致有些人将台湾芯片产业称为「硅盾」(silicon shield),认为可以吓阻中国的攻击,并且确保美国提供支持。

经济部长王美花在9月受访时曾告诉路透社,半导体产业与台湾的未来密切相关。她表示:「这不仅关乎我们的经济安全。这看来也攸关我们的国家安全。」

之后,经济部发表声明淡化所谓的「硅盾」理论。声明说:「与其说芯片产业是台湾的『硅盾』,称台湾在全球供应链占有重要位置会更适当」。

路透社提到,对台湾的危险之处在于,台积电晶圆厂处于火在线。这些工厂位于台湾西岸、面朝中国的狭窄平原上,而两岸最近距离仅约130公里。

位于新竹的台积电总部和周边晶圆厂离岸边只有12公里,而这些工厂多数靠近所谓的「红色海滩」(red beaches),即军事战略家认为中国入侵时可能的登陆地点。

报导提到,台湾半导体产业的脆弱性在去年7月暴露出来,当时台湾动员数以千计部队仿真对抗中国攻击,地点是产业重镇台中市,即台积电超大晶圆厂第15厂所在地,是制造先进芯片的代工厂之一。在演习中,中国入侵行动遭到击退。

经济部被问及岛上晶圆厂面临的威胁时表示,「过去50年来,中国从未放弃试图以武力控制台湾,但目标不是半导体产业」,台湾有能力「面对及管理这项危机」。

Taiwan chip industry emerges as battlefront in U.S.-China showdown

The island dominates production of the chips that power almost all advanced civilian and military technologies. That leaves the U.S. and Chinese economies extremely reliant on plants that would be in the line of fire in an attack on Taiwan. It’s a vulnerability stoking alarm in Washington.

By YIMOU LEE, NORIHIKO SHIROUZU and DAVID LAGUE

12/27/2021

TAICHUNG, Taiwan – On the front line of the superpower struggle between the United States and China, Taiwan has fashioned a defensive masterstroke. It has become indispensable to both sides.

In dominating the fabrication of the most advanced semiconductors, the giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Ltd (TSMC) has captured a technology that’s crucial to the cutting-edge digital devices and weapons of today and tomorrow. TSMC accounts for more than 90% of global output of these chips, according to industry estimates.

Both superpowers now find themselves deeply dependent on the small island at the center of their increasingly tense rivalry.

For Washington, allowing an increasingly powerful China to overrun TSMC’s foundries in a conflict would threaten U.S. military and technological leadership. However, if Beijing invades, there is no guarantee it could seize the prized foundries intact. They could easily become a casualty of the fighting, severing the supply of chips to China’s vast electronics industry. Even if the foundries survived a Chinese takeover, they would almost certainly be cut off from a global supply chain essential to their output.

“The big concern in Washington is the possibility of Beijing gaining control of Taiwan’s semiconductor capacity.”

Martijn Rasser, a former senior intelligence officer and analyst at the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

Both America and China want to break their dependency. Washington has persuaded TSMC to open a U.S. foundry that will make advanced semiconductors and is preparing to spend billions rebuilding its domestic chip-making industry. Beijing, too, is spending big, but its chip industry lags a decade or so behind Taiwan’s in many key areas. Analysts say that gap is expected to widen in the years ahead.

So valuable are these foundries to the global economy that some here refer to Taiwan’s chip sector as a “silicon shield” that deters a Chinese attack and ensures American support.

In an interview, Taiwan Economy Minister Wang Mei-hua told Reuters in September that the industry is deeply intertwined with the island’s future.

“This isn’t just about our economic safety,” she said. “It appears to be connected to our national security, too.”

In a later statement, the ministry played down the silicon-shield theory. “Rather than saying that the chip industry is Taiwan’s ‘Silicon Shield,’” the statement said, “it is more appropriate to say that Taiwan has an important position in the global supply chain.”

The danger for Taiwan is that TSMC’s fabs, as the chip fabrication plants are known, are right in the line of fire.

The foundries are located on the narrow plain along Taiwan’s west coast facing China, some 130 kilometers away at the nearest point. Most are close to so-called red beaches, considered by military strategists as likely landing sites for a Chinese invasion. TSMC’s headquarters and surrounding cluster of fabs at Hsinchu in northwest Taiwan are just 12 kilometers from the coast.

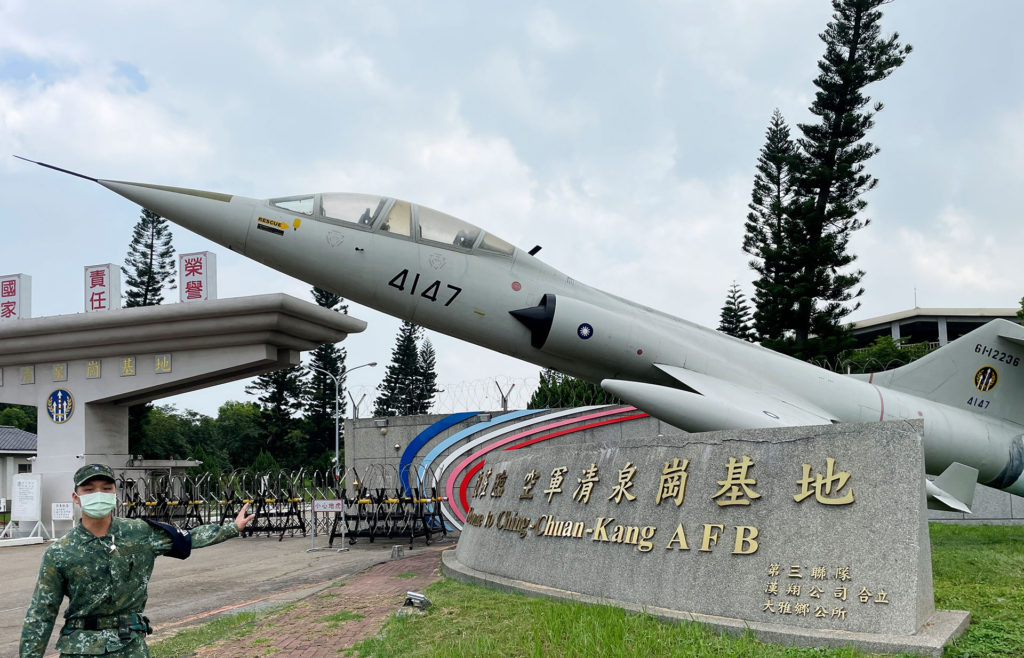

The industry’s vulnerability was on display in July last year, when Taiwan mobilized thousands of troops to fight off a simulated Chinese attack on the west coast industrial city of Taichung, home to TSMC’s Gigafab 15, one of the foundries that make cutting-edge chips.

In the counter-invasion exercise, “enemy” paratroopers dropped on Ching Chuan Kang air base and captured the control tower, just nine minutes’ drive from Gigafab 15. Off the coast, a virtual Chinese invasion flotilla steamed towards the city’s beaches. Fighting enveloped Taichung as Taiwanese troops and tanks counterattacked to regain control of the air base; commanders called in airstrikes, missiles and artillery, using live ammunition to pound the “invasion fleet.” The invasion was repulsed.

In mocking the exercise scenario, reports in China’s state-controlled media reinforced the potential for destruction: Waves of missile strikes would destroy the island’s forces before a Chinese landing, they said.

China’s defense ministry and the Taiwan Affairs Office didn’t respond to questions for this story.

Asked about the threat to the island’s fabrication plants, the Taiwan economy ministry said that in “the past 50 years, China has never given up trying to use force to control Taiwan, but its aim is not the semiconductor industry.” Taiwan, it added, had the ability to “face and manage this risk.”

TSMC did not answer specific questions about the exposure of its foundries. In a statement, it emphasized that the chip industry is global and relies on design, raw materials, equipment and other services from several regions and many specialized companies. “Therefore, rather than one company or one region, global collaboration is vital for semiconductor industry success,” the company said.

AMERICAN ANXIETY

As China ratchets up its military intimidation of Taiwan, Washington is signaling anxiety over U.S. chip dependency.

“The big concern in Washington is the possibility of Beijing gaining control of Taiwan’s semiconductor capacity,” said Martijn Rasser, a former senior intelligence officer and analyst at the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. “It would be a devastating blow for the American economy and the ability of the U.S. military to field its (weapon) platforms,” said Rasser, now a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

In one of the Biden administration’s clearest statements on the need to resist a Chinese attack on Taiwan, a top Pentagon official told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Dec. 8 that the island’s semiconductors were a key reason why Taiwan’s security was “so important to the United States.”

A spokesperson for the White House National Security Council had no comment on the chip vulnerability, but said Washington “would regard any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific.”

Taiwan’s chip supremacy, while clearly a strategic advantage, might not be enough to deter China from trying to take the island by force, some warn.

The deep economic interdependence among the nations of Europe failed to prevent war in 1914, said retired U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant General Wallace Gregson, a former assistant secretary of defense in the Obama administration. While the semiconductor industry is “thoroughly beneficial” to the island’s security, Gregson said, it’s questionable whether this would prevent conflict once the “dogs of war get loose.”

What’s more, he added, Chinese President Xi Jinping has staked his legacy on bringing Taiwan under Beijing’s control. “He can’t be seen to compromise, much less back down,” Gregson said. “He is tied to this achievement.”

At risk for China and America is access to chips that power almost all advanced military and civilian technologies, including mobile phones and the medical diagnostic and research tools that have been invaluable in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

The most advanced chips, which are critical in the U.S.-China arms race, are those described as 10 nanometers or below – the sector dominated by Taiwan. These tiny devices pack billions of electronic components in an area as small as a few square millimeters.

While the semiconductor industry is “thoroughly beneficial” to Taiwan’s security, it’s questionable whether this would prevent conflict once the “dogs of war get loose.”

Retired U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant General Wallace Gregson

A major U.S. worry is losing ground in the race to use artificial intelligence in weaponry. AI enables machines to outperform humans at solving problems and making decisions. It is expected to revolutionize warfare, and it hinges on semiconductors.

In a March report to Congress, the bi-partisan National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence warned that the threat to TSMC exposed a glaring vulnerability. Taiwan produced the “vast majority of cutting-edge chips” a short distance from America’s “principal strategic competitor,” the report said. “If a potential adversary bests the United States in semiconductors over the long term or suddenly cuts off U.S. access to cutting-edge chips entirely, it could gain the upper hand in every domain of warfare.”

Much is at stake for Beijing, too. The loss of chips from Taiwan would crush Chinese industry. China accounts for 60% of world semiconductor demand, according to an October 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service. More than 90% of semiconductors used in China are imported or manufactured locally by foreign suppliers, the report said.

BREAKFAST BREAKTHROUGH

Taiwan’s rise as chip power dates back to a breakfast in early 1974 at a downtown Taipei eatery known for its soy milk and steam buns, according to an account by the island’s Industrial Technology Research Institute.

A Chinese-born executive from a leading U.S. tech company, Radio Corporation of America, discussed a bold idea with Taiwanese officials: Build a semiconductor industry from scratch on the island. Taipei struck a tech-transfer agreement with RCA and sent engineers to work there.

“Back then, no one knew these technologies would become so important,” said Chen Liang-gee, who served as Taiwan’s Science and Technology Minister until May 2020.

In 1985, Chinese-born engineer Morris Chang, a 25-year veteran of another U.S. semiconductor power, Texas Instruments Inc, was recruited to head technology development in Taiwan. In 1987, Chang founded TSMC with the government as the major shareholder.

Chang made a decision that reshaped the global industry: He decided that TSMC would be a pure foundry, making chips for other companies. Orders poured in from Western makers who wanted to focus on design and cut costs.

Today, TSMC has the eleventh-highest market capitalization of any listed business. This year, it plans to outlay about $30 billion in capital investment, dwarfing Taiwan’s $16 billion defense budget.

In a speech in Taipei in April, Chang likened Taiwan’s chip industry to a “holy mountain range protecting the country,” a phrase popular in Taiwan that is used to describe TSMC’s pivotal role in the island’s economy. “I used it to make my point that it would be very difficult for Taiwan to create another company with TSMC’s influence,” Chang told Reuters.

Taiwan now accounts for 92% of the world’s most advanced semiconductor manufacturing capacity, according to the April report from Boston Consulting and the Semiconductor Industry Association. South Korea holds the remaining 8%.

THE CHALLENGE FOR CHINA

Early on, Taiwan protected this crown jewel. In the late 1990s, then-President Lee Teng-hui imposed curbs on the island’s high-tech companies doing business in China to ensure they didn’t offshore their best technology. The restrictions have been relaxed, but TSMC and its peers remain barred from building their most advanced foundries in China.

“Looking back now, the industry supply chain could have been entirely moved there,” said Chen, the former Taiwan tech minister.

Under Xi, China has set a goal of self-sufficiency in manufacturing advanced chips – what some have dubbed the “great semiconductor leap forward.” The Taiwanse curbs aren’t the only obstacle to Xi’s vision. Also at play are two other factors: a U.S.-led effort to limit tech transfers to China, and the sheer complexity of fabricating advanced semiconductors.

America and its allies have for decades imposed chip technology barriers on China, mostly aimed at curbing Beijing’s development of advanced weaponry. The United States maintains a list of specific chip technology that requires a license for export, and restricts tech exports to China’s leading chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation. SMIC did not respond to questions from Reuters.

The controls on SMIC are tailored to block items needed to produce advanced chips of 10 nanometers or smaller. So far, China mostly produces lower-end chips for consumer electronics.

A key tool in this containment strategy: the Wassenaar Arrangement, a voluntary pact among 42 nations to curb the spread of “dual-use” technology, with both commercial and military applications. Under Wassenaar, Washington and its allies have harmonized controls over the flow of chip technology to China.

The most significant restriction is on equipment that uses extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light beams. This light is generated by lasers and focused by mirrors to lay out ultra-thin circuits on silicon wafers. EUV is at the bleeding edge of semiconductor manufacturing. It allows chipmakers to build faster and more powerful microprocessors and memory chips.

According to Kevin Wolf, a former assistant secretary of commerce in the Obama administration, the EUV curbs are aimed at blocking China’s effort to produce 5 nanometer chips – today’s state of the art – or even more advanced semiconductors now under development.

For China’s economic planners, semiconductor independence is a top priority. The aim is what’s known as a “closed loop,” analysts say, with domestic companies responsible for the entire sector: raw materials, research, chip design, manufacturing and packaging.

This is a huge challenge for any economy because the existing global supply chain for chips is so complex – involving hundreds of materials and chemicals, more than 50 types of high-tech equipment, and thousands of suppliers across Europe, North America and Asia.

A Biden administration review of U.S. supply-chain vulnerability reported in June that Beijing was directing $100 billion in subsidies to its chip industry, including the development of 60 new plants. Some of this spending has already led to huge losses, however, with a spate of bankruptcies, loan defaults and abandoned projects.

Even if China were able to acquire foreign technology and direct money into better-run projects, there’s no guarantee it would succeed in advanced chips, say U.S., Japanese, Dutch and Taiwanese semiconductor industry veterans.

Advanced chip making is among the most complex manufacturing processes yet devised, they say. Fabricating chips takes three to four months and over a thousand manufacturing processes. It must be done in a pristine environment and requires precision equipment that manipulates particles on sub-atomic levels.

China also faces a talent gap. It has recruited engineers and technicians from Taiwan, South Korea and America. But these efforts have yet to deliver major breakthroughs. Companies like TSMC have huge teams of specialists for a vast array of processes. Poaching individual experts can only deliver gains in niches of the craft, industry executives say.

These elite professionals are the most important asset of Taiwan’s chip industry, says retired navy Captain Chang Ching, a research fellow at the Taipei-based Society for Strategic Studies. “If it invades Taiwan, the Communist army will do its best to protect the personnel working in the tech sector,” he said.

Having relinquished chip fabrication to Taiwan, America is now trying to reverse that move. The U.S. AI commission called for the government to spend $35 billion in incentives to rebuild a chip manufacturing industry.

But Taiwan says it has no intention of surrendering primacy.

TSMC has begun trial production of what will be its most advanced chip, using so-called 3-nanometer technology. And it has launched an R&D drive to make 2-nanometer chips.

Between now and 2025, local and foreign companies plan to invest more than T$3 trillion ($108 billion) in Taiwan’s chip industry, according to Kung Ming-hsin, head of the island’s economic planning agency, the National Development Council.

After this splurge on factories and equipment, Kung said, “Taiwan’s semiconductor industry will have very few competitors.”

A Taiwan Crisis May Mark The End Of The American Empire

By Niall Ferguson

7/09/2021

In a famous essay, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin borrowed a distinction from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

“There exists,” wrote Berlin, “a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to … a single, universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance” — the hedgehogs — “and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory” — the foxes.

Berlin was talking about writers. But the same distinction can be drawn in the realm of great-power politics. Today, there are two superpowers in the world, the U.S. and China. The former is a fox. American foreign policy is, to borrow Berlin’s terms, “scattered or diffused, moving on many levels.” China, by contrast, is a hedgehog: it relates everything to “one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision.”

Fifty years ago this July, the arch-fox of American diplomacy, Henry Kissinger, flew to Beijing on a secret mission that would fundamentally alter the global balance of power. The strategic backdrop was the administration of Richard Nixon’s struggle to extricate the U.S. from the Vietnam War with its honor and credibility so far as possible intact.

The domestic context was dissension more profound and violent than anything we have seen in the past year. In March 1971, Lieutenant William Calley was found guilty of 22 murders in the My Lai massacre. In April, half a million people marched through Washington to protest against the war in Vietnam. In June, the New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers.

Kissinger’s meetings with Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier, were perhaps the most momentous of his career. As a fox, the U.S. national security adviser had multiple objectives. The principal goal was to secure a public Chinese invitation for his boss, Nixon, to visit Beijing the following year.

But Kissinger was also seeking Chinese help in getting America out of Vietnam, as well as hoping to exploit the Sino-Soviet split in a way that would put pressure on the Soviet Union, America’s principal Cold War adversary, to slow down the nuclear arms race. In his opening remarks, Kissinger listed no fewer than six issues for discussion, including the raging conflict in South Asia that would culminate in the independence of Bangladesh.

Zhou’s response was that of a hedgehog. He had just one issue: Taiwan. “If this crucial question is not solved,” he told Kissinger at the outset, “then the whole question [of U.S.-China relations] will be difficult to resolve.”

To an extent that is striking to the modern-day reader of the transcripts of this and the subsequent meetings, Zhou’s principal goal was to persuade Kissinger to agree to “recognize the PRC as the sole legitimate government in China” and “Taiwan Province” as “an inalienable part of Chinese territory which must be restored to the motherland,” from which the U.S. must “withdraw all its armed forces and dismantle all its military installations.” (Since the Communists’ triumph in the Chinese civil war in 1949, the island of Taiwan had been the last outpost of the nationalist Kuomintang. And since the Korean War, the U.S. had defended its autonomy.)

With his eyes on so many prizes, Kissinger was prepared to make the key concessions the Chinese sought. “We are not advocating a ‘two China’ solution or a ‘one China, one Taiwan’ solution,” he told Zhou. “As a student of history,” he went on, “one’s prediction would have to be that the political evolution is likely to be in the direction which [the] Prime Minister … indicated to me.” Moreover, “We can settle the major part of the military question within this term of the president if the war in Southeast Asia [i.e. Vietnam] is ended.”

Asked by Zhou for his view of the Taiwanese independence movement, Kissinger dismissed it out of hand. No matter what other issues Kissinger raised — Vietnam, Korea, the Soviets — Zhou steered the conversation back to Taiwan, “the only question between us two.” Would the U.S. recognize the People’s Republic as the sole government of China and normalize diplomatic relations? Yes, after the 1972 election. Would Taiwan be expelled from the United Nations and its seat on the Security Council given to Beijing? Again, yes.

Fast forward half a century, and the same issue — Taiwan — remains Beijing’s No. 1 priority. History did not evolve in quite the way Kissinger had foreseen. True, Nixon went to China as planned, Taiwan was booted out of the U.N. and, under President Jimmy Carter, the U.S. abrogated its 1954 mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. But the pro-Taiwan lobby in Congress was able to throw Taipei a lifeline in 1979, the Taiwan Relations Act.

The act states that the U.S. will consider “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” It also commits the U.S. government to “make available to Taiwan such defense articles and … services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capacity,” as well as to “maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

For the Chinese hedgehog, this ambiguity — whereby the U.S. does not recognize Taiwan as an independent state but at the same time underwrites its security and de facto autonomy — remains an intolerable state of affairs.

Yet the balance of power has been transformed since 1971 — and much more profoundly than Kissinger could have foreseen. China 50 years ago was dirt poor: despite its huge population, its economy was a tiny fraction of U.S. gross domestic product. This year, the International Monetary Fund projects that, in current dollar terms, Chinese GDP will be three quarters of U.S. GDP. On a purchasing power parity basis, China overtook the U.S. in 2017.

Read More…

傅立民文章:中美竞争最终将如何收场

5/12/2021

核心提示:文章指出,如果美国被中国和“世界其他国家的崛起”逼下台,那也是因为自满的美国人未能让一种曾经成功过的制度去适应解决政治和经济积弊,并为新突破奠定基础。中国和其他国家与此毫不相干。

参考消息网 5月11日报道 俄罗斯《全球政治中的俄罗斯》双月刊网站5月3日发表题为《中美对抗将如何收场》的文章,作者为美国布朗大学沃森国际与公共事务研究所客座研究员、美国前助理国防部长傅立民。全文摘编如下:

现在,美国在所有方向上开始与中国竞争,人们不清楚这种竞争将把我们带向何方。在我们开展深入探讨之前,应当先思考几个关键问题:中美的赌注有多大?双方在已开始的斗争中将动用哪些现有战术能力和未来战略能力?长期竞争会对双方造成何种可能的影响?这场斗争最终将如何收场?

中美各有核心利益诉求

那么,让我们把过去视为客观现实并努力专注于未来。

中国政治精英认为,有五样基本的东西值得一赌:

一是彻底打消欧洲和日本帝国主义肢解中国的企图,以及美国以冷战方式实施干涉并策动台湾独立的念头;

二是为弥补过去中国国家尊严所受屈辱而争取地位和尊严;

三是严格防范可能破坏中国稳定并损害中国利益和领土完整的行动以及外国军事干预的发生;

四是让中国顺利重返其在遭受欧洲帝国主义干涉前所占据的经济和技术高地;

五是在地区和全球事务中扮演符合中国体量及其日益增强的国力的角色。

美国的政治精英也在五个方面投下赌注:

一是让美国维持其在全球和地区的政治、军事、经济和金融领先位置;

二是保住美国作为印太等地区中小国家可靠军事保护国的所谓“声誉”;

三是维护美国在所谓“世界秩序”中的优越性;

四是通过降低对不受美国及其盟国控制的供应的依赖来获得经济安全;

五是实现再工业化、提高高收入岗位的就业率,并恢复国内平静的社会经济形势。

现在,中美两国间的力量平衡正在迅速变化,而且趋势对美国不利。今天的中国拥有比美国更广泛的国际联系。它已成为包括欧盟在内的世界上大多数经济体的最大贸易伙伴,在全球贸易和投资中的领先优势不断扩大。中国在全球科技创新中发挥的作用越来越大,而美国的阵地却越来越小。

盟友未必唯美马首是瞻

中国崛起首先带来的是经济而非军事方面的挑战。自冷战结束10年后至今,我们从未在中美关系中看到过类似今天的敌对状态。今天的中国军队有能力保卫自己的国家免遭任何外国攻击。

值得庆幸的是,中国依旧竭力通过谈判而非军事手段的方式解决台湾问题。而这样的谈判可以确保和平的延续。目前,中国的战略目标是提高美国向亚太地区投射力量的成本,但并不直接威胁美国。

拜登承认:为了有效与更加强大的中国开展协作,需要强化自己的立场并争取别国的帮助。为此,他在政府测试国会有关消除美国自身弱点的意愿并与盟友及伙伴进行磋商前,迟迟未出台有关对华政治经济和军事路线的决策。

但如果美国当局听从那些希望与中国对抗的人士的意见,那么它会意外地发现,并不是很多人赞成这么做。拜登可能面临复杂的政治选择:要么弱化对中国的敌意以争取第三国支持,要么坚持对抗立场而不惜疏远大多数欧洲和亚洲盟国。

现实情况是:欧洲人感受不到来自中国的所谓“军事威胁”,而东南亚和南亚国家认为台湾问题是中国人的内部事务并竭力置身事外。甚至像日本这种对台当局“地位”有着直接战略关切的国家也不想冒险介入冲突。

实力对比正向中国倾斜

中美实力不对称状况的转变可能让形势变得更复杂,过去长期为美国带来优势的经济、技术和军事力量对比现在正向有利于中国的方向发展。

在社会转型初期,迎来了基于科学的新产业浪潮。这些产业包括人工智能、量子计算机、云分析、数据库、安全区块链等等。中国向科研和教育设施及开发和应用这些技术的劳动力资源投入巨资。相反,美国目前则面临长期预算赤字,因为政治僵局和没完没了的战争让华盛顿背上沉重的财政负担。这种局面如不扭转,中国和其他国家将很快令美国失去一个世纪以来在科技和教育领域的全球主导地位。

即使美国克服当前政治机能失调和财政赤字,中国在科技、工程和数字领域的崛起也将对美国全球和地区主导权构成挑战。这是一个多方面的问题,美国在解决这个问题时,有时会弄巧成拙。比如,将北京排除在国际太空合作之外,结果,中国发展自己的航天能力。

今天,美国极力阻止中国在5G网络占据优势,反倒促使中国建立有竞争力的半导体产业。人类历史表明,任何技术突破迟早都会以这样或那样的方式被复制,而且成果只会比原先更好。

最大威胁并非来自对手

付出的大量战略努力扩大和升级了中美之间不可调和的矛盾。双方都认为对手是其崩溃的可能原因。然而,最大威胁实际上来自国内趋势和事件,而非外国势力的行动。中美的世界地位取决于它们在国际舞台上如何行事,而非对手的行动。

如果美国被中国和“世界其他国家的崛起”逼下台,那也是因为自满的美国人未能让一种曾经成功过的制度去适应解决政治和经济积弊,并为新突破奠定基础。

美国在全世界的声望下降和追随者减少,与美国的国内政治事件、战略失误、对盟国和伙伴的公然蔑视、虚伪专断的制裁、作为主要外交工具的胁迫和低效外交有关。中国和其他国家与此毫不相干。

现在,为了与中国竞争,美国在很多方面也在借鉴北京建立的制度。华盛顿呼吁实行工业化政策,大幅增加科研开支,以及设立基础设施投资的特别银行和基金等。

Sino-American Antagonism: How Does This End?

Remarks to the Confucius Institute, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho

Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr. (USFS, Ret.)

Visiting Scholar, Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs, Brown University

By video link from Washington, D.C.

15 April 2021

Fifty-three years ago, as a young foreign service officer, I helped ensure that Taipei rather than Beijing continued to represent China in the United Nations Security Council and elsewhere internationally. Since then, I have seen relations between China and the United States evolve from mutual ostracism based on stereotypes that bore little resemblance to reality to varying degrees of cooperation and mutual understanding and back again. Now we’re once again off to the races in all sorts of struggles with China with nary a clue where any of them will take us.

It seems to me that before we get too far along this path, we ought to pause to think a bit about a few key questions. These have been strikingly absent from our policy debate. Specifically:

- What are the stakes for China and for the United States respectively?

- What current tactical and future strategic capabilities does each bring to the fight we’ve now begun?

- What are the likely consequences for each side of protracted struggle with the other?

- How are these struggles most likely to turn out?

So, in my remarks today, I’ll take the past as given and try to focus on the future.

The Chinese political elite appears to believe that five main things are stake:

- A final reversal of the carve-up of China by European and Japanese imperialism, warlordism, the Chinese Civil War, and America’s Cold War intervention to separate Taiwan from the rest of the country.

- Status and “face” (self-esteem fed by the deference of others) that offset past foreign insults to national dignity.

- Assured defense against foreign “regime change” operations or military interventions that could threaten the rule of the Chinese Communist Party, China’s return to wealth and power, or the consolidation of China’s claimed frontiers.

- China’s uninterrupted return to the high economic and technological status it enjoyed before its eclipse by European imperialism.

- A role in the management of the affairs of the Indo-Pacific region and the world commensurate with China’s size and burgeoning capabilities.

The American political elite also appears to believe that what’s at stake[1] is five things:

- U.S. retention of global and regional politico-military, economic, technological, and monetary primacy.

- America’s reputation as the reliable military protector of lesser states in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere.

- American paramountcy in a world order guided by the liberal democratic norms professed by the European Enlightenment and the American Revolution

- Economic security through reduced dependence on supply chains not controlled by the United States or countries beholden to it.

- Reindustrialization, higher levels of well-paying employment, and the restoration of domestic socioeconomic tranquility.

The People’s Republic of China came into being seventy-two years ago. For over one-third of its existence, the United States has been actively committed to the overthrow of its “Communist” government. That appears once again to be a hope, if not an explicit objective, of U.S. policy.

China and the United States have never been evenly matched except in self-righteousness, unwillingness to admit error, and a tendency to scapegoat each other. But, in many respects, the balance between the two countries is now rapidly shifting against America. The world expects China to regain its historical position as one-third to two-fifths of the global economy. China already has an economy that produces about one-third of the world’s manufactures and that is – by any measure other than nominal exchange rates – larger than that of the United States. President Trump’s trade and technology wars convinced the Chinese that they had to reduce reliance on imported foreign technologies, develop their own autonomous capabilities, and become fully competitive with America.

China is now in some ways more connected internationally than the United States. It is the largest foreign trade partner of most of the world’s economies, including the world’s largest – the European Union (EU). Its preeminence in global trade and investment flows is growing. The 700,000 Chinese students now enrolled in degree programs abroad dwarf the less than 60,000 students from the United States doing the same American universities still attract over one million foreign students annually but nearly half a million international students now opt to study in China. China’s role in global science and technological innovation is growing, while America’s is slipping. Chinese have come to constitute over one-fourth of the world’s STEM workers. They lead the world in patent applications by an increasingly wide margin.

Only four percent of American schools offer classes in Mandarin, but (with increasing competence) all Chinese schools teach English – the global lingua franca – from the third grade. America’s xenophobic closure of Chinese government-sponsored “Confucius Institutes” promises to cripple even the current pathetic level of student exposure to the Chinese language in U.S. schools. Meanwhile, the increasingly unwelcoming atmosphere on U.S. campuses has reduced applications by Chinese and other foreign students to American universities, especially in the physical sciences and engineering.[2]

The challenges posed by the rise of China are clearly more economic than military, but China and the United States are now locked in a level of armed hostility not seen since the first decade of the Cold War. Back then, U.S. forces dedicated to “containing” the People’s Republic and championing the rival Chinese regime on Taiwan were incomparably more modern and powerful than the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Chinese forces were arrayed to resist an anticipated American attack they knew they could not defeat. The U.S. Cold War policy of containment blocked China from effectively asserting ancient claims to islands in its near seas, while opening the way for other claimants to occupy them.

The Chinese military can now defend their country against any conceivable foreign attack. They also appear to be capable of taking Taiwan over American opposition – even if only at tremendous cost to themselves, Taiwan, and the United States. It is disquieting that Beijing now judges that intimidation is the only way to bring Taipei to the negotiating table. But it is reassuring that China still strives for cross-Strait accommodation rather than military conquest of Taiwan and its pacification. The U.S. forces deployed along China’s coasts are there to deter such a conquest. But their presence also has the effect of backing and bolstering Taiwan’s refusal to talk about – still less negotiate – a relationship with the rest of China that might meet the minimal requirements of Chinese nationalism and thereby perpetuate peace.

The danger is that, with the disappearance of any apparent path to a nonviolent resolution of the Taiwan issue, China could conclude that it has no alternative to the use of force. It would not be surprising for it to calculate that to hold America at bay, it must match U.S. threats to it with equivalent threats to the United States. This is, after all, the strategic logic that, during the Cold War, led the Soviet Union to match the missiles the United States had deployed to Turkey with its own in Cuba. No one should rule out the possibility that Sino-American relations are headed toward an eventual reprise of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

America has long been in China’s face. The way things are going, in the future, China may also be in America’s. In the meantime, the aim of Chinese strategy is to raise the costs of American trans-Pacific power projection against it, not to threaten the United States.

President Biden has recognized that to deal effectively with an increasingly formidable China, the United States must strengthen itself as well as enlist the help of other countries. He has therefore deferred immediate decisions about what politico-economic and military China policies he should adopt until his administration can test the willingness of Congress to redress American weaknesses and can consult with allies, partners, and friends abroad. But, if Washington listens to those it seeks to recruit as auxiliaries in its opposition to China, it will discover that few of them share the all-out animus against China to which so many Americans have become committed. President Biden may well find he faces a hard political choice between whether to moderate American hostility to China to garner third country support, or to stick with confrontational policies that separate the United States from most of its European and Asian allies.

The awkward reality is that Europeans do not feel militarily threatened by China. Southeast and South Asians see Taiwan as a fight among Chinese from which they should keep their distance. By contrast with Taiwanese, they fear intimidation, not conquest by China. Even those countries, like Japan, with a direct strategic interest in the status of Taiwan don’t want to risk being drawn into a fight over it.

The Taiwan issue is a legacy of the Chinese civil war and U.S. Cold War containment policies. America’s allies look to Washington to manage it without reigniting conflict between the island and the rising great power on the Chinese mainland. If the U.S. does end up in a war with China, America is likely to be on its own or almost so.

To further complicate matters, past asymmetries are in the process of reversing themselves as balances of economic, technological, and military power that long favored Washington shift in favor of Beijing. The Greeks invented the concept of a “Europe” distinct from what they called “Asia.”[3] Chinese connectivity programs (the “Belt and Road”) are recreating a single “Eurasia.” Many countries in that vast expanse see an increasingly wealthy and powerful China as an ineluctable part of their own future and prosperity. Some seem more worried about collateral damage from aggressive actions by the United States than about great Han chauvinism. Few find the injustices of contemporary Chinese authoritarianism attractive, but fewer still are inclined to bandwagon with the United States against China.

By 2050, China is predicted to have a GDP of $58 trillion – almost three times larger than America’s today and more than two-thirds greater than the then-projected U.S. GDP of $34 trillion. China’s rapidly aging population leaves it with no apparent alternative to Japanese-style domestic automation and the offshoring of labor-intensive work to places that still have fast-growing working-age populations, like Africa. China is investing heavily in robotics, medicine, synthetic biology, nanobot cells and other technologies that can enhance and extend the productive lives of the aged. It is also adjusting and expanding its social security and public health systems. The United States faces analogous challenges, aggravated by increasingly xenophobic immigration policies, acceptance of mediocrity in education, crumbling infrastructure, and the pyramiding of national debt to finance routine government operations as well as correctives to damage from past self-indulgence. Americans talk about these problems but have yet to address them.

A wave of new science-based industries is in the early stages of transforming human societies. Examples include artificial intelligence, quantum computing, cloud analytics, blockchain-protected databases, microelectronics, the internet of things, electric and autonomous vehicles, robotics, nanotechnology, genomics, biopharmaceuticals, 3D/4D and bio-printing, virtual and augmented reality, nuclear fusion, and the synergies among these and other emerging technologies.

China is making major investments in the scientific and educational infrastructure and workforce needed to lead the development and deployment of most of these technologies. By contrast, at present, the United States is in chronic fiscal deficit, immobilized by political gridlock, and mired in never-ending wars that divert funds needed for domestic rejuvenation to the Pentagon. America’s human and physical infrastructure is already in sad condition, and it is deteriorating. If these weaknesses are not corrected, China and others will soon eclipse the century-long U.S. preeminence in global science, technology, and education. Or, as President Biden put it, China “will eat our lunch” and “own the future.”

Even if the United States overcomes its current political dysfunction and fiscal malnutrition, the upsurge in Chinese science, technology, engineering, and mathematics capabilities promises to challenge America’s retention of global as well as regional primacy. The competition is not limited to the Asia-Pacific region. It is multifaceted, and, in attempting to deal with it, the United States has sometimes been too clever by half – for example, excluding Beijing from international cooperation in space. This has led to an increasingly robust set of indigenous Chinese space-based capabilities, many of which are of military relevance.

Similarly, the U.S. effort to head off Chinese dominance of 5-G communications is now spurring the creation of a globally competitive semiconductor industry in China. In the short term, the Chinese microelectronics manufacturing sector faces great difficulties. It is always easier to buy things than to learn to make them. But, in the longer term, China has the will, the talent, the wherewithal, and the market to succeed. Human history is full of proofs that, one way or another, sooner or later, every technological advance can and will be duplicated, often with results that surpass the original.

The PLA has copied American practice by harnessing commercial technological innovation to military purposes. Its 军民融合 or “military-civil fusion” program recognizes that market-driven research and development and university-led innovation frequently outpace in-house efforts by the military establishment. As the United States did before it, China is linking industry and academia more closely to its national defense. The pace at which China develops innovative military applications from civilian-developed technology now promises to accelerate.

In response to U.S. military dominance of its periphery, China has invested in anti-ship, anti-air, counter-satellite, electronic warfare, and other capabilities to defend against a possible American attack. Some Chinese weapons systems break new ground – among them terminally-guided ballistic missile systems to kill carriers, quantum communications devices, naval rail guns, and stealth-penetrating radar. In the event of armed conflict, the PLA can now effectively block U.S. access to China’s near seas, including Taiwan.

The PLA Navy has many more hulls than the United States, its ships are more modern, some of its weapons have greater range, and its home-based battlefield support is much closer to the potential war zone. Chinese industry’s surge and conversion capacities now vastly exceed those of the United States. In any future war with China, the U.S. armed forces cannot expect to enjoy the technological superiority, information dominance, peerless capacity to replenish losses, and security of bases and supply lines they have had in past wars.

The strategic effects of the broadening and escalating antagonism between the United States and China have already been considerable. Let me cite some examples.

- It is dividing the world into competing technological ecospheres that are beginning to produce incompatible equipment and software, a reduction in globally traded goods and services, and an accelerated decline in American dominance of high-tech industries.

- It is generating an active threat to the U.S. dollar’s seven-decade-long command of international trade settlement. Increased use of other currencies menaces both the efficacy of U.S. sanctions and the continued exemption of the American economy from balance of trade and payments constraints that affect other countries.

- It has distorted and possibly destroyed the global “rules-bound order” for trade, helping to proliferate sub-global, non-inclusive free trade areas and forcing the development of ad hoc rather than institutionalized multilateral trade dispute resolution mechanisms.

- It is hampering global cooperation on planetwide problems like pandemics, climate change, environmental degradation, and nuclear non-proliferation. (For a time, scapegoating of China served to divert attention from a pathetically ineffectual U.S. domestic response to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

- It is pushing China and Russia into a broadening entente (limited partnership for limited purposes). It may now be driving Iran into affiliation with this dyad.

- It has helped to replace diplomacy with offensive bluster, blame games, and bullying that lower respect for both China and America in other countries, while imposing painful collateral damage on nations like Canada and Australia.

- It has brought about an alarming rise in the danger of a war over Taiwan, while accelerating both conventional and nuclear arms races between China and the United States.

There is no sign that either side intends to change course. Nine-in-ten U.S. adults are now hostile or ill-disposed toward China. Chinese hostility to the United States has risen to comparable levels.

To be sure, popular views are both ill-informed and fickle. And at least as many things could go wrong as go right for both China and the United States. The January 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol is a reminder that scenarios that once seemed preposterous can yet occur. Both China and the United States face internal as well as external challenges. This is a moment of fragility in the life of both countries. Game-changing events are not impossible to imagine.

In the near term, for example:

- A reversal of progress in countering the global pandemic could bring about a collapse in the global economy and lead to widespread unemployment and political unrest in both China and the United States.

- The death of the Dalai Lama could destabilize Sino-Indian relations. Beijing might find itself at war with New Delhi, which lusts to reverse its 1962 humiliation by the PLA, and which is once again aggressively probing the de facto border between the two countries. A Chinese defeat in the Himalayas could catalyze a disruptive change in China’s leadership. A victory could lead to Chinese strategic ebullience as well as Indian abandonment of nonalignment in favor of entente with the United States.

- A war in the Middle East or a crisis in Korea could challenge America while offering China an apparent opportunity to strike at Taiwan with relative impunity.

- The emergence of less prudent leadership in Taipei could lead to decisions there that impel Beijing to invoke its 2005 anti-secession law and use force to recover Taiwan despite an expectation that the United States would intervene.

- Other events involving Taiwan, such as a return of U.S. forces and installations to the island or the revelation of yet another Taiwanese nuclear weapons program, could trigger a Chinese use of force.

- The division, disorder, demoralization, partisanship, political gridlock, and uncontrolled immigration now troubling the United States could force Washington to focus on restoring domestic social order at the expense of attention to foreign commitments.

- The death or incapacitation of the top leader in either China or the United States could lead to disputes over succession that weaken government authority and decision-making, distracting and inviting miscalculation by one or the other side.

Of course, none of these things may happen, but the fact that they are not unimaginable underscores the shakiness of current strategic realities.

In the somewhat longer term, still other developments could alter the course of the contest. For example:

- Chinese “wolf warrior” diplomacy and economic bullying may so thoroughly alienate other countries that, to the extent they can, they turn their backs on China and join the United States in opposing it.

- Beijing’s obsession with political control could – not for the first time in China’s long history – suffocate its private sector and stifle innovation.

- China’s semiconductor, artificial intelligence, and robotics companies will either succeed or fail in their drive to outperform their American, Taiwanese, and other competitors. If they succeed, their competitors’ industries could be hollowed out and China could dominate cyberspace and related domains. If they fail, China will fall behind.

- Aging in China and a reversion to xenophobic immigration policies in the United States could reduce working-age populations, damage productivity, slow growth, and increase the welfare burden in either or both societies, forcing reductions in “defense” outlays and generating pressure for mutual disengagement from military confrontation.

- Chinese and other experiments with digital currency trade settlement could dethrone the dollar from its post-World War II global hegemony, force the United States to bring its balance of payments and trade into equilibrium, lower U.S. living standards, and greatly reduce American international power.

- Beijing’s brutal efforts to assimilate minorities to Han culture may not only fail but alienate Muslim and other foreign partners, while remaining a cause célèbre in the West, and empowering a broad international effort to ostracize China.

- The cognitive dissonance between Washington and allied capitals about China and other issues could effectively gut America’s alliances, leaving the United States isolated in its hardline decoupling from China.

- Japan might go nuclear, altering the calculus of deterrence in Northeast Asia, and enabling it to declare strategic autonomy from the United States without forgoing American non-nuclear protection.

- The United States and the Russian Federation could replace their current mutual hostility with an entente directed at balancing and constraining Chinese power.

- Climate change could not only inundate major Chinese and American coastal cities (like Shanghai and New York) but also lead to natural disasters like crop failures, super storms, floods, forest fires, and the devastating displacement of populations, leaving little enthusiasm and fewer resources in either country for competition with the other.

- Conversely, disunity at home could lead demagogues in either China or the United States to rally patriotic support by pursuing aggressive policies abroad.

- A failure to reforge mechanisms for international cooperation on public health issues could allow new pandemics to overwhelm national capacities to resist them.

- The PLA Navy could match the U.S. Navy’s deployments along China’s coasts with its own deployments along America’s, deterring U.S. intervention in China’s near abroad while creating the preconditions for an agreement by which each side would pull some or all of its forces back to its own side of the Pacific.

Few or none of these game-changing developments may happen. But they reveal the stakes both sides and the world at large have in finding ways to wind down the adversarial antagonism that has now gripped Sino-American relations.

Each side has come to see the other as the possible cause of its downfall. But each is actually more menaced by trends and events in its homeland than by what any foreign power might do to it. The position of each in the world depends more on how it conducts itself internationally than on how the other does. In a world in which power and influence are unevenly distributed not just between the U.S. and China but also among lesser players in world affairs, neither China nor the United States can expect to exercise unchecked dominance at either the regional or global level. China will not displace America from international primacy, but neither will America be able to retain primacy.

If China falters, it will not be because the United States has opposed it but because Beijing has adopted self-corroding policies and practices that obviate the successes of “reform and opening,” alienate foreign partners, and impair further progress. Mao’s China was a failure in terms of returning China to wealth and power but laid the basis for Deng Xiaoping to set aside ideological rigidities and sponsor the eclectic adaptation of international best practices to Chinese circumstances. Changes in Beijing’s domestic policies, the entrepreneurial energy these released, and the foreign relationships they enabled explain the differences between China from 1949 to 1979 and China from 1979 forward. Policies can determine outcomes.

To develop, Beijing has declared, China needs a “peaceful international environment.” It is bordered by 14 countries, four of which are nuclear-armed and four of which harbor unresolved territorial disputes with it. Its civil war with recalcitrant forces on Taiwan has not concluded. Japan and the United States, two countries with which China has been at war in still-living memory, are unreconciled to its renewed wealth and power. These factors place China on the defensive and constrain any impulse on its part to project its power beyond its periphery. To practice market Leninism successfully, China needs friends.

Deportment helps determine friendships. “Friends” are either (1) the rare comrades you would yield your own life to save and whom you expect would do the same for you; (2) partners who will go out of their way to do you a favor as you would for them; (3) companions whose presence you enjoy but with whom you share no real commitment; (4) sycophants who want something from you and strive to ingratiate themselves with you to get it; and (5) parasites who seek cunningly to exploit their association with you for their own interests without regard to yours.

The Chinese people are widely admired abroad. But there is no enthusiasm for either global or regional leadership by China’s government. Others acknowledge its accomplishments, but few find it appealing. As the Chinese phrase puts it, 笑里藏刀—their smiles conceal daggers. Insincere attachments that rest on sycophancy or parasitism are flattering but do not embody respect and are neither reliable nor steadfast. They can conceal disdain, create liabilities, and invite perfidy.

If China continues to allow its security services and diplomats to browbeat foreigners and treat other countries in the arrogantly abrasive and bullying manner it has recently adopted, the only international relationships it will have will be hypocritical, scheming, and untrustworthy. Many abroad will fear China, but none will faithfully support it, few will follow it, and some will opt to oppose it. China will “lose face.” And, when “face” is at stake, China has a well-established record of irrational reactions that make it its own worst enemy.

Similarly, if the United States is eclipsed by China and “the rise of the rest,” it will be because Americans, mired in complacency, failed to adjust a once brilliantly successful system to address accumulated politico-economic problems and lay a basis for resumed advance. China can neither compel America to reform nor stop it from doing so. Americans alone can reaffirm their constitution, fix their broken politics, restore competence to their government, strengthen their society by reducing its economic and racial inequities, rejuvenate the competitiveness of their capitalism, abide by the norms of international conduct they seek to impose on others, respect international diversity and other countries’ sovereignty, and discard militarism in favor of diplomacy.

The ongoing slippage in U.S. prestige and followership internationally owes far more to self-disfiguring American domestic developments, strategic blunders, open contempt for allies and partners, sanctimoniously high-handed sanctioneering, offensively coercive foreign policies, and self-implemented diplomatic disarmament than it does to an imagined onslaught on the preexisting global order by China or others. The Punch and Judy show put on by senior American and Chinese diplomats at Anchorage played well back home in both countries. It did not inspire foreign confidence in the wisdom or capacity for empathy of either side.

China achieved much of its post-Mao developmental success by applying ideas learned from America. In many respects, in the name of competing with China, the United States is now turning to copying elements of the resulting Chinese system. Politicians in Washington are calling for industrial policies; major ramp-ups in spending on science and technology; the creation of specialized banks and funds dedicated to infrastructure investment; national security-derived protectionism, subsidies; and preferential licensing for key technologies and national champion companies; and what amounts to currency manipulation to produce a cheaper dollar.

The United States also appears to be progressively adopting aspects of Beijing’s intolerant and intrusive definitions of political correctness and “national security,” even if Washington still leaves internet censorship and the manipulation of public opinion to corporate oligopolies rather than imposing government controls. But there is no need to point this out to those attending this session of the Confucius Institute at the University of Idaho. Some of you have personally experienced the “cancel culture” built into the latest round of Sinophobia in the United States.

American populism’s strategic dementia now competes with Chinese exceptionalism’s imperious demeanor. To one degree or another, in both countries, groupthink has become the enemy of constructive engagement. Each side’s resentment of its alleged past or current victimization at the hands of the other adds bitterness to the equation. Only Beijing’s habitual risk aversion now averts a bloody U.S. rendezvous with Chinese nationalism in a war over Taiwan.

All things being equal, if there is no war over Taiwan or other game-changing event, current trends – American protectionism, decoupling from supply chains connected to China, and cognitive dissonance with allies and partners – seem more likely to continue than to halt. This suggests a future in which:

- China’s neighbors and the many dozens of countries participating in its Belt and Road Initiative draw steadily closer to Beijing economically and financially. Brave talk notwithstanding, the United States no longer has the open markets, financial resources, or engineering capabilities to counter this. Washington has shown no capacity to sustain the level of diplomatic engagement with the countries of the Indo-Pacific, Central Asia, East Africa, Russia, or EU members states needed to match Beijing. It is failing to do so even in Latin America. You can’t best something with nothing other than rhetoric and, for now, that’s effectively all the United States is offering.

- As the division of the global market into separate trade and technological ecospheres proceeds, China will take the global lead in a widening list of consequential new technologies. Its scientific and technological achievements will attract foreign investors and corporate collaborators regardless of their misgivings about China’s political system. Where markets remain open to them, Chinese companies – state-owned and private – will compete successfully for market share with American, European, Japanese, and Korean companies.

- The growth in Chinese power – combined with persistent concerns about erratic behavior by America’s wounded democracy – will cause major regional powers like India, Indonesia, and Japan to develop regional coalitions, defense industrial cooperation projects, and collaborative diplomacy designed to balance China — with or without the United States.

- As its naval and air power expand, China will consolidate its military dominance of its periphery. Americans will be forced to think twice about intervening to protect Taiwan from PLA coercion or controlling China’s near seas. Armed clashes with the Chinese Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Forces are conceivable. These could either undermine or stiffen American willingness to escalate hostilities with China.

- The domestic and foreign purchasers of U.S. government debt could conclude that it is backed by little more than “modern monetary theory” and cease to buy it. This alone would end the “exorbitant privilege” of the United States, deprive Washington of the ability to enforce unilateral sanctions, and make the American dominance of the Indo-Pacific economically unsustainable.

- Taiwan’s increasing military vulnerability and dependence on mainland Chinese markets for its continued prosperity could compel it to negotiate a relationship with the rest of China sufficient to appease the demands of Chinese nationalism.

China seems confident that some of these or similar scenarios will unfold in the decades to come. Its strategic confidence and resolve contrast with a lack of similar conviction in America, where short-term cluelessness, enforced by fiscal fecklessness, still rules the day. The challenges to American status and presuppositions from China are real. They will not be overcome with fantasy foreign policies based on unrealistic assessments of current and future circumstances.

A deeply imbedded faith in liberal democratic ideology led some Americans to theorize that, given enough exposure to the United States, Chinese political culture would inevitably evolve into a version of America’s. That this did not happen was not a failure of “engagement,” as American Sinophobes would have it. China’s retention of its own authoritarian political culture reflects its system’s delivery of results that more than satisfied the material needs of the Chinese people while restoring their pride in their nation. What’s happened in China may or may not disprove theories about the inevitability of political liberalization in middle-class societies. This deserves reflection. But so does the thesis that, without fundamental domestic reform, the United States can outcompete a China that is rising on its own terms, not America’s, in a world in which the United States no longer calls the shots.

The future of China will be made or unmade in China. The future of the United States will be made or unmade in America. Neither is foreordained.

[1] See, e.g., Senator Tom Cotton’s articulation of U.S. objectives vis-à-vis China: https://www.cotton.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/210216_1700_China%20Report_FINAL.pdf

[2] https://www.nationalacademies.org/ocga/testimonies/116-session-1/maintaining-us-leadership-in-science-and-technology

[3] https://chasfreeman.net/the-challenge-of-asia/

Source: https://chasfreeman.net/sino-american-antagonism-how-does-this-end/

China beating US by being more like America

Cultivating human capital will be essential if the US rather than China is to be the base of the next industrial revolution

By BRANDON J WEICHERT

4/25/2021

The United States transitioned from an agrarian backwater into an industrialized superstate in a rapid timeframe. One of the most decisive men in America’s industrialization was Samuel Slater.

As a young man, Slater worked in Britain’s advanced textile mills. He chafed under Britain’s rigid class system, believing he was being held back. So he moved to Rhode Island.

Once in America, Slater built the country’s first factory based entirely on that which he had learned from working in England’s textile mills – violating a British law that forbade its citizens from proliferating advanced British textile production to other countries.

Samuel Slater is still revered in the United States as the “Father of the American Factory System.” In Britain, if he is remembered at all, he is known by the epithet of “Slater the Traitor.”

After all, Samuel Slater engaged in what might today be referred to as “industrial espionage.” Without Slater, the United States would likely not have risen to become the industrial challenger to British imperial might that it did in the 19th century. Even if America had evolved to challenge British power without Slater’s help, it is likely the process would have taken longer than it actually did.

Many British leaders at the time likely dismissed Slater’s actions as little more than a nuisance. The Americans had not achieved anything unique. They were merely imitating their far more innovative cousins in Britain.

As the works of Oded Shenkar have proved, however, if given enough time, annoying imitators can become dynamic innovators. The British learned this lesson the hard way. America today appears intent on learning a similar hard truth … this time from China.

By the mid-20th century, the latent industrial power of the United States had been unleashed as the European empires, and eventually the British-led world order, collapsed under their own weight. America had built out its own industrial base and was waiting in the geopolitical wings to replace British power – which, of course, it did.

Few today think of Britain as anything more than a middle power in the US-dominated world order. This came about only because of the careful industrial and manipulative trade practices of American statesmen throughout the 19th and first half of the 20th century employed against British power.

The People’s Republic of China, like the United States of yesteryear with the British Empire, enjoys a strong trading relationship with the dominant power of the day. China has also free-ridden on the security guarantees of the dominant power, the United States.

The Americans are exhausting themselves while China grows stronger. Like the US in the previous century, inevitably, China will displace the dominant power through simple attrition in the non-military realm.

Many Americans reading this might be shocked to learn that China is not just the land of sweatshops and cheap knockoffs – any more than the United States of previous centuries was only the home of chattel slavery and King Cotton. China, like America, is a dynamic nation of economic activity and technological progress.

While the Chinese do imitate their innovative American competitors, China does this not because the country is incapable of innovating on its own. It’s just easier to imitate effective ideas produced by America, lowering China’s research and development costs. Plus, China’s industrial capacity allows the country to produce more goods than America – just as America had done to Britain

Once China quickly acquires advanced technology, capabilities, and capital from the West, Chinese firms then spin off those imitations and begin innovating. This is why China is challenging the West in quantum computing technology, biotech, space technologies, nanotechnology, 5G, artificial intelligence, and an assortment of other advanced technologies that constitute the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Why reinvent the wheel when you can focus on making cheaper cars and better roads?

Since China opened itself up to the United States in the 1970s, American versions of Samuel Slater have flocked to China, taking with them the innovations, industries, and job offerings that would have gone to Americans had Washington never embraced Beijing.

America must simply make itself more attractive than China is to talent and capital. It must create a regulatory and tax system that is more competitive than China’s. Then Washington must seriously invest in federal R&D programs as well as dynamic infrastructure to support those programs.

As one chief executive of a Fortune 500 company told me in 2018, “If we don’t do business in China, our competitors will.”

Meanwhile, Americans must look at effective education as a national-security imperative. If we are living in a global, knowledge-based economy, then it stands to reason Americans will need greater knowledge to thrive. Therefore, cultivating human capital will be essential if America rather than China is to be the base of the next industrial revolution.

Besides, smart bombs are useless without smart people.

These are all things that the United States understood in centuries past. America bested the British Empire and replaced it as the world hegemon using these strategies. When the Soviet Union challenged America’s dominance, the US replicated the successful strategies it had used against Britain’s empire.

Self-reliance and individual innovativeness coupled with public- and private-sector cooperation catapulted the Americans ahead of their rivals. It’s why Samuel Slater fled to the nascent United States rather than staying in England.

America is losing the great competition for the 21st century because it has suffered historical amnesia. Its leaders, Democrats and Republicans alike, as well as its corporate tycoons and its people must recover the lost memory – before China cements its position as the world’s hegemon.

The greatest tragedy of all is that America has all of the tools it needs to succeed. All it needs to do is be more like it used to be in the past. To do that, competent and inspiring leadership is required. And that may prove to be the most destructive thing for America in the competition to win the 21st century.

Source: https://asiatimes.com/2021/04/china-beating-us-by-being-more-like-america/