The Economic Ruin of the Roman Empire

Posted by Hannah S. Bowers in Ancient History

By Nick Anderson

4/08/2021

Throughout the centuries historians have tried to explain why the Roman Empire fell. In 1984, Alexander Demandt, a German historian, provided a list of two hundred and ten reasons for Rome’s decline, including some entertaining ideas like gout, earthquakes, and female emancipation. The overall view of most historians has been that Rome reached its zenith in the second century, started to decline in the third, and finally collapsed in the fifth. Historians credit A.D. 476 with the official demise of the western empire. Rome fell through a gradual process because poor economic policies led to a weakened military which allowed the barbarians easy access to the empire.

In the third century, Rome’s emperors embraced harmful economic policies which led to Rome’s decline. First, the limitation of gold and silver resources led to inflation. Monetary demand caused emperors to mint coins with less gold, silver, and bronze. For example, Emperor Claudius II debased the silver denarius to only one-fiftieth of its original value. Currently, the price of gold is $1,722 per ounce, but if the government appraised an ounce of gold for $34, then inflation would be the same as the Roman third century. Emperors thought to fix inflation by issuing price control laws, but the laws were below equilibrium prices, thus hurting the economy further. During the fourth century, Constantine successfully reformed the currency, but other poor economic policies continued within the empire.

Secondly, excessive upper-class wealth hurt the Roman economy. Some wealthy individuals hoarded gold bullion because of the dramatic inflation in the third century. Others, like Emperor Commodus, depleted the imperial coffers so the empire had little money left. The wealthy upper-classes enjoyed a combination of unlimited economic and political power, and such excessive wealth led to a poverty state in the western empire which crippled its effort to maintain a strong military system.

The third problem Rome’s economy faced was tax increases. Rome acquired money for taxation by gaining new lands. However, the empire reached its territorial limits by the time of Emperor Trajan in the second century. As Rome lost eastern lands to invaders, the loss of that taxable income meant tax increases for the western provinces. Also, any loss of land due to immigrants directly affected imperial tax revenues. Even if they were not conquered, provinces where fighting occurred struggled to pay taxes. By the early fifth century, Rome had lost Britain, Spain, and parts of southern Italy. As the Roman state lost financial power, landowners realized their lifestyle was threatened by increased taxation and property laws. Many of these landowners turned to the politics of Rome to protect their holdings. In return for tax revenue, Rome agreed to protect the landowning class from outside enemies, but tax increases continued for the lower classes.

Rome’s poor economic policies caused military problems. First, the decreased tax base meant no financial support for the military. The Roman military cost fifty percent of the imperial expenses. By the mid-fifth century the army had been bled dry by declining tax revenues so they were mere shadows along the borderlands. Even though the eastern military had defeated their invaders, the army was forced to stay in the Middle East to keep the peace. The weakened military in the west failed to stop the barbarian groups as they cut out chunks of land for themselves across the empire. More troops were needed for the professional army, but the funds could not be raised. The strength of the army was directly tied to the tax base.

A second military problem, caused by hiring low-pay soldiers, resulted in poor training and discipline. Rome’s army had always been small compared to the empire’s population, but the training and discipline had been unrivaled by all contestants. As mercenaries and volunteers joined the ranks, discipline completely changed. Trained Roman soldiers now protected themselves behind a wall of shields and let mercenaries rush out for hand-to-hand combat. As the western army became more barbarized, it lost military tactics. Also, a large portion of the military transitioned to garrison forces who dealt primarily with minor threats to frontier security. These soldiers had many other local duties and lived in a communal setting with their wives and children. When the barbarians began to push with force, the garrisons were not strong enough to fight back because they lacked man-power and training.

Thirdly, economic problems influenced prolonged military commands. Generals claimed they needed more time to end military campaigns successfully, so the Senate granted them prolonged military commands, and inevitably, these commands moved troop loyalty to the commander. Generals now became the main contenders for imperial power, taking their armies away from the borders in pursuit of Roman glory.

Finally, economic problems led the military to employ mercenary soldiers. The Senate approved of mercenaries because the extent of the empire was taxing native soldiers. The larger the empire grew, the more heavily Rome relied on mercenaries to guard its borders and rogue territories. These mercenaries claimed no allegiance to Rome and thus followed their commander because he paid them. Barbarian soldiers, known as the foederati, gained Roman protection and privileges in return for protecting the empire’s borders, and these foederati eventually made up eighty percent of the army. The Roman military thus weakened over time, and they continued to lose territories along the borderlands which further damaged the Roman economy. This vicious cycle persisted until the barbarian invasions destroyed the empire in the fifth century.

Ultimately, Rome declined because poor economic policies led to a weakened military. When pressures grew along the borders, Rome lacked the resources to defeat the enemies of the past. No territorial conquests were available to provide new wealth for a dying economy forcing Rome to finally yield to the barbarian invasions. So instead of considering why Rome fell, perhaps historians should side with Edward Gibbon and be surprised that Rome lasted so long.

– Hannah S. Bowers

Bibliography

The Heritage of the World: with a Western Emphasis. New York: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2010.

Kagan, Donald. The End of the Roman Empire: Decline or Transformation? Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath and Company, 1992.

Ward-Perkins, Brian. The Fall of Rome: and the End of Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. Ebook.

Source: https://coffeeshopthinking.wordpress.com/2013/01/05/the-economic-and-military-decline-of-rome/

罗马帝国的衰亡 – 货币和经济角度的考量

By Yifan Knows Nothing

4/08/2021

1776年的英国出版了两本历史上举足轻重的著作:亚当史密斯的《国富论》和 爱德华吉本 的《罗马帝国衰亡史》。

早年简单看过后者这本大作,认为吉本对罗马帝国衰亡的解读主要集中在皇帝个人执政行为和宗教这两方面,尽管分析详细,但对衰亡原因的理解过于狭隘。而随着近现代考古发现的不断增加,罗马帝国的研究更加集中在社会、经济和军事领域,其中,对货币和经济的研究则成为近年来的重点。

现代对罗马经济金融史研究的学者已经对以下观点达成一致,认为导致罗马帝国的崩溃的主要原因是通货膨胀,导致政府最终无力支付军队,从而无法抵抗外敌入侵。至于通货程度,举了例子,公元前共和体制时期,50 银币(罗马主要流行货币denarius银币)可以支付罗马一家人一年的食物,而到了3世纪,获得等量的食物则需要6000银币。货币超发则通过皇帝一次次把银币含银量降低而完成,一单位银币的含银量从Augustus公元前1世纪的95%降到到公元后3世纪的0.5%。

罗马皇帝超发货币目的是为了维持政府开支。军队、对外战争、罗马市民的身份地位和国家荣耀,在我看来,是维系罗马帝国团结稳定的四个主要支柱。然而,军队稿赏、对外战争开支和体现国家荣耀的市政工程,都需要大量财政支持。因此,最终导致超发货币和通货膨胀的内在原因,可以理解为罗马皇帝和精英们在处理军队、养老金、战争、国家荣耀和国家财政之间关系时,缺乏对其内在逻辑联系的认识,并犯了一些列错误。

首先,军队的扩充是基于养老金的保证。罗马帝国为了维持和扩张疆土,需要保持军队的规模;而最普遍的征兵手段是通过养老金来吸引公民加入军队,并希望能通过战争减员,从而减少未来养老金的债务。但问题是一旦帝国完成扩展、进入全盛和平时期,军队数量则不会减少,最后一批新加入军人不会被战争减员,其养老金则成为未来不可避免的巨大债务。帝国军队人数,从公元前300年的不足5万人,增加到公元后300年的近40万人,并在30万人的高位保持了从公元后100年到公元后300年,将近200年。罗马研究学者阿姆斯特朗认为,正是养老金的持续增加,导致货币超发,最终引发通货膨胀的结果,让罗马皇帝最终无力支付军队并败给了那些有能力支付野蛮人雇佣军的外族部落。可以说,持续告诉增加的军队养老金和无法高速增加货币的供应之间的矛盾是导致罗马帝国衰退的最主要原因。事实上,后期罗马帝国衰退过程的缓解很大程度上是得益于Trajan时期扩张时发现的银矿。

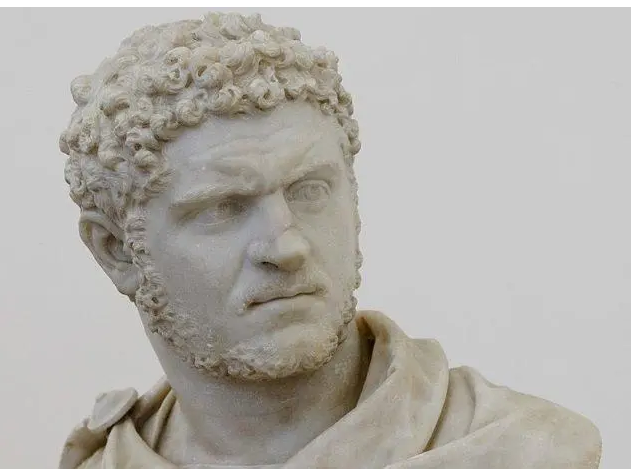

另一方面,用金钱奖赏军队的坏习惯由早期的皇帝们开了先河。随后,每一位新皇帝继位,首先要争取军队对其皇位的效忠,于是对军队进行稿赏。当年Caracalla曾说“除我以外,任何人都不应拥有大量货币。这样我就可以集中财富来供养军队。”他也真的说到做到,在扩大征税人口的同时,将军队收入提高了50%。习惯了高收入的军队随后被金钱彻底腐败,以致于在古罗马帝国后期,军队中的禁卫军将领暗杀了前任皇帝,并公开要价,哪位候选人出价高,禁卫军便拥护他做继承人。新当任的皇帝由于害怕被禁卫军和军队暗杀夺权,便更加依赖金钱来收买军队,从而维护政局稳定。Claudius,在公元1世纪,为暗杀前任所支付禁卫军的报酬是3千5百万的denarii银币,而到了公元2世纪,Commodus收买禁卫军的总计支出高达5.7亿denarii银币。这时的denarii银币往往就是铜币在银水里过一下沾一层银,一块银币中银的含量从公元前的2克,下降到当时的不足0.3克。至此,除养老金外,稿赏和收买军队让整个军队体系在财政支出中的占比越发增大。后期的皇帝开始尝试裁剪禁卫军,但努力往往都以失败或被暗杀告终。

同时,货币超发本身没有带来皇帝想要的结果。一方面,随着银币的不断贬值,民众也聪明的用含银量较低的新货币来交税,而把含银量较高的老货币收藏起来。这样,皇帝发行货币的一个初衷,即用低值货币换取高值货币,没能实现。这恐怕也是格雷欣的劣币驱逐良币法则的最早验证。与此同时,稀有金属金银的供给受制于自然界中的已探明开采储量,在政府开支增加的同时,皇帝只能通过不断稀释货币中贵金属含量,来增发货币。

另一方面,一部分罗马皇帝们寄希望于战争来获取更多稀有金属、并减少军队人口数量从而降低其养老金债务,但是战争本身会减少货币的流通,大量出土的深埋地下的古罗马钱罐证明了一点,随着战乱的加剧,尽管货币发行增加,民众却减少消费并增加储蓄。由于当时不存在现代银行体系,当时的储蓄就意味着流通货币的减少,这势必负面影响了国家经济和政府财政。(当然,即时今天,这种现象同样存在;当未来的不确定较大时,储蓄率的上升似乎是人类的自然社会行为反应。)

最后,由于财政收入的基础是罗马公民的税收,罗马皇帝们为了扩大税收,往往会进一步扩大公民的人数和范围。而公民的广泛扩大暂时增加了税收,却降低了罗马公民的社会地位,间接降低了公民的国家荣誉和认同感。如此,导致公民对皇帝权力的认可完全基于政府持续的货币供应从而维持社会经济的繁荣,如此财政负担进一步加重。

至此,可以看到,古罗马皇帝们过于依赖军队的政治哲学,使军队成为古罗马帝国的一个肿瘤,其养老金和效忠赏赐让财政入不敷出。为了缓解该紧张局面,皇帝们扩大税收基础人口、提高税率和增发货币。扩大税收和税费导致公民的国家荣誉感降低,使其统治更依赖于经济繁荣来*收*买*民*心*。而货币增发作为经济繁荣的发动机,其不可避免的后果是罗马帝国的通货膨胀,间接导致军队对稿赏的需求同比增加。因此,罗马帝国进入一个*金*钱*收*买*军*队*效*忠、货币增发和通货膨胀相互刺激增长的恶性循环。最后当帝国没有足够财力去满足军队时,军队自然无法没有足够动力参与战争,而外族部落则有足够的黄金去雇佣野蛮人参战。

The Rise and Decline of Nations

By Mancur Olson

4/08/2021

“The Rise and Decline of Nations” put forth Mancur Olson’s theory to explain macroeconomic growth. Why do some countries grow quickly and others slowly? Why do some countries grow quickly at some times and slow at others? Though he doesn’t claim that it is the only factor, he answers that a main reason for this effect is that over time, in stable countries with unchanged boundaries, distributional coalitions (interest groups, collusive organizations) start to form and grow. The longer the country is stable, the more distributional coalitions it will have. These groups influence politics to gain benefits for their group, thereby imposing economic inefficiencies on the country. Collusive groups of businesses may set prices higher than the market rate. These inefficiencies slow growth in these countries. In countries that undergo upheaval (Germany and Japan after WWII, for example), these coalitions are broken down, and once they are stable again, these countries will have a high growth rate for a period of time. He applies this theory to countries around the world, uses it to suggest an explanation for the caste system in India and apartheid in South Africa, and uses it to explain unemployment throughout time and stagflation in the 1970s.

1. The Questions, and the Standards a Satisfactory Answer Must Meet

A satisfactory theory about macroeconomic growth must be able to explain why there are different growth rates at different times and in different places – it can’t simply explain one issue. It should match up with microeconomic theory, so it is possible to understand why individuals are making particular decisions. In general, a good theory should be parsimonious (short) and explain a lot.

2. The Logic

In Olson’s previous book, “The Theory of Collective Action,” he explains how and why groups form. In general, it is difficult to form groups for collective action if there is no way to exclude people from the benefits. Any member could refuse to participate, and not make any contribution, but that member would still benefit from the work of the group. (For example, if you’re fixing up a neighborhood park, one person may not help fund or work on the park, but others won’t be able to keep that person from using the park when it’s finished.) This is called the ‘free rider’ problem. Furthermore, if the benefits to each group member don’t exceed the costs each pays, they will not take any action. From this understanding, Olson argues that smaller groups are easier to form than larger groups. He also suggests a number of ways that people can be influenced to join groups. One is social pressure – if there are small groups of people that know each other, there can be pressure on individuals not to be “free riders.” Another is selective incentives. Selective incentives are things that are provided to members, but not to non-members – it could be a magazine, special insurance rates, or any other item that can be provided only to group members.

Six Spaces Home Staging

Contact: Hongliang Zhang

Tel: 571-474-8885

Email: zhl19740122@gmail.com

3. The Implications

Building on the logic about groups presented in the second chapter, Olson lays out nine implications that form the basis of his theory, which is used to explain particular situations in the rest of the book.

1. There will be no countries that attain symmetrical organization of all groups with a common interest and thereby attain optimal outcomes through comprehensive bargaining. Essentially, through groups will continue to be created and grow over time, the power will never even out so that the groups perfectly represent society and don’t hurt efficiency – some, the poor, consumers, and other dispersed groups, will not be as well represented.

2. Stable societies with unchanged boundaries tent to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time. The longer the country is stable, the more distributional coalitions they’re going to have.

3. Members of “small” groups have disproportionate organizational power for collective action, and this disproportion diminishes but does not disappear over time in stable societies. It’s easier for small groups to form, and the benefits they can each get from redistributing wealth (through political action) to their own small group is greater than the benefit that each member of a larger group would get from redistributing the same amount of wealth. Basically, interest groups are more likely to represent a relatively small group of farmers, industries, etc., rather than large dispersed groups like consumers, the poor, etc.

4. On balance, special-interest organizations and collusions reduce efficiency and aggregate income in the societies in which they operate and make political life more divisive. It is more beneficial for the groups to spend money to redistribute wealth to themselves (through political lobbying or collusion), rather than increasing overall efficiency of the economy (investing in new technologies, etc.), since the redistributions go only to their small group while the overall efficiencies would benefit the economy as a whole. The involvement of many special interest groups in politics makes issues more divisive and complex.

5. Encompassing organizations have some incentive to make the society in which they operate more prosperous, and an incentive to redistribute income to their members with as little excess burden as possible, and to cease such redistribution unless the amount redistributed is substantial in relation to the social cost of the redistribution. If an organization represents a very large group of society, then the benefits of overall economic growth may be more beneficial than redistribution. An example is a national labor union, which may be more interested in economic growth and creating more jobs, rather than protecting one particular type of job.

6. Distributional coalitions make decisions more slowly than the individuals and firms of which they are comprised, tend to have crowded agendas and bargaining tables, and more often fix prices than quantities. Since there is so much bargaining, lobbying, and other interactions that need to occur among groups, the process moves more slowly in reaching a conclusion. In collusive groups, prices are easier to fix than quantities because it is easier to monitor whether other industries are selling at a different price, while it may be difficult to monitor the actual quantities they are producing.

7. Distributional coalitions slow down a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions, and thereby reduce the rate of economic growth. Since it is difficult to make decisions, and since many groups have an interest in the status quo, it will be more difficult to adopt new technologies, create new industries, and generally adapt to changing environments.

8. Distributional coalitions, once big enough to succeed, are exclusive, and seek to limit the diversity of incomes and values of their membership. Since any benefits that are gained through lobbying or collusion need to be shared among the members of the group, once the group is large enough to be successful, it will not want to admit more members. For example, if a small number of companies has a monopoly over a particular market, it will be in their interest to make it difficult or impossible for new-comers to enter their market, so they can maintain their monopoly benefits.

9. The accumulation of distributional coalitions increases the complexity of regulation, the role of government, and the complexity of understandings, and changes the direction of social evolution. As the number of distributional coalitions grows, it will make policy-making increasingly difficult, and social evolution will focus more on distributing wealth among groups than on economic efficiency and growth.

4. The Developed Democracies Since World War II

The implications discussed above suggest that a country that has just undergone major upheaval, once it is stable again, will experience increased economic growth. This is the case in the “miracle” economies in Germany and Japan after WWII. It is not surprising, under this theory, that countries such as Britain had relatively slow postwar growth, since they had been stable over a long period and had a large number of distributional coalitions. He also looks at the growth of various states within the U.S. over time, finding that in the 1960s and 70s, the states in the west and south had higher growth rates than those in the northeast. This agrees with the theory, since the northeastern states have existed and been stable for the longest period of time.

5. Jurisdictional Integration and Foreign Trade

Though the theory would make it seem that occasional upheaval or revolution would be beneficial to economic growth, that is not the policy implication that Olson aims to provide. He notes that similar benefits can be had by opening boarders – i.e. implementing free trade. He gives the example of France (and many other countries) which in medieval times was broken into largely autonomous towns and cities. There were often tariffs imposed by each city, and tolls imposed to pass through them. In each town, the people who practice a particular art could fairly easily collude – these were the medieval artisan’s guilds. Olson uses these guilds to illustrate implication 8 – that once groups are big enough to succeed, they aim to limit their membership. Therefore, once guilds were formed, increasingly strict rules were put into place to ensure it was difficult for outsiders to join the profession. People could only begin the profession if they first became an apprentice. In many cases, each professional was only allowed one apprentice. In this way, the guilds were able to maintain multi-generational monopolies in their occupation in each of the autonomous towns. When national monarchs began to take more control and removed the tariffs and tolls, it was difficult for the guilds to maintain their monopolies – people could buy in other towns for less, and even if sellers tried to keep the monopoly in their town, they’d have an incentive to sell in another town at a price under-cutting that town’s guild. This breakdown of barriers put distributional coalitions into disarray and allowed countries to have a period of more rapid growth. Similar effects are seen after the creation of the European Union and even after unilateral free trade decisions.

6. Inequality, Discrimination, and Development

Though it is more difficult to get historical data, Olson argues that the theory applies not only to Europe, but to all parts of the world. He gives the example of guilds that existed in ancient China and India. He even suggests the theory could help to explain why India’s caste system has seemed to grow more rigid. He argues that the castes were similar to occupational guilds, and that rules such as endogamy (only marrying within the group) were put into place to keep the power of the group over multiple generations (limiting the size of the group once it is successful – implication 8). Ensuring people only marry within their caste ensures that the group does not mix and become so large that the benefits to each member would be diminished. Encouraging prejudice among groups reinforces the rules for interacting and marrying only within the group. He gives a very similar explanation for apartheid in South Africa. He argues that when the Boers first came to South Africa, the separation between white and black was not as extreme, and there were a number of mixed-race relations. In the beginning, mining companies hired cheaper, black laborers for the unskilled labor and hired the more expensive, white workers for the semi-skilled and skilled positions. The mining companies, however, then believed that it would be in their interest to provide the black laborers with some training so that they could take over some of the semi-skilled and skilled jobs at lower wages, thus decreasing costs for the mining companies. However, the white laborers started lobbying the government to pass legislation setting wages for semi-skilled and skilled jobs. Legally imposed high wages meant there was no incentive for mining companies to train or hire black workers for semi-skilled or skilled jobs. Additional laws were passed, increasingly separating white and black, with the aim (implication 8 again) to keep the interest group from growing, now that it was successful. Political efforts were paired with other things, such as endogamy within groups and cultivating prejudice to keep the powerful group from expanding. Olson argues this evolved into the strict apartheid regime.

7. Stagflation, Unemployment, and Business Cycles: An Evolutionary Approach to Macroeconomics

When both high inflation and unemployment occurred in the 1970s, it went against many of the prevailing economic theories – Keynesian theory suggested inflation and unemployment could not happen simultaneously, and traditional monetary theory had no explanation for long periods of unemployment. Olson suggests this phenomenon can be explained using the theory presented in this book. He notes that the result and reaction to depressions had been changing over time. He compares the crisis in 1839-43 to the great depression in 1929-1933. In the earlier period, the contraction in money supply was greater and the fall in the price level was substantially greater, both of which would suggest the effects would be worse in the earlier period. However, in the earlier period, real consumption was positive, while in the second period, it was negative. Similarly, in 1839-43, the real GNP rose, while in 1929-33, the real GNP fell. Olson argues that the growth of collusive organizations and distributional coalitions was the cause of this difference. In a crisis, it is best if wages and prices are flexible, so that employers can offer lower wages and employees get jobs at lower wages, but still continue producing things and continue working. However, if there are labor unions that insist a wage stay set at a high level, then the wage is not flexible, and employers and employees can’t make mutually beneficial agreements to work together at lower wages – less people can be employed and the system is less efficient. This was the case in the great depression. In this situation, all of the people who can’t get jobs try to move to industries that do have flexible wages. In the great depression, many people tried to move to farming, for example, but since there were so many people moving into this area, it flooded the market, and the value of farm goods decreased significantly, so that people couldn’t make a good wage in this area either. Olson argues that this trend continues, so that unemployment and inefficiency become more and more of a problem during crisis over time in stable societies.

Source: http://marieljohn.blogspot.com/2010/02/rise-and-decline-of-nations.html

罗马帝国衰亡的经济因素

By 小西

4/07/2021

有一派史学观点认为,罗马帝国的形成,本质上是在顺应环地中海贸易圈融合的一种内在需求。埃及的粮食、高卢的铁矿、伊比利亚的美酒、希腊的玻璃、陶瓷,所有这些商品为了达成流通成本的最小化,都在呼唤一个稳定的统一国家出现。

而罗马城刚好处于这个“全球化1.0版”的贸易圈的正中央。于是罗马治下的和平(Pax Romana)应运而生了,它为维护帝国境内所有生产者、贸易者的生产和财产安全而存在。所以罗马帝国前期的工商营业税(对那个时代来说)是非常低廉的,各行省之间商品流通的关税只有1.5%一5%关税(从东方进口的奢侈品要征收25%)、各种手工作坊的营业税只有1%。蓬勃发展的工商业,不仅为帝国提供了强大的经济后盾,更给这个帝国的存在提供了理由——商业需要流通,产品需要市场,帝国治世是他们最好的选择,人们当然乐于接受的这个制度。

但不幸的是,罗马帝国有它摆脱不了的诅咒——它的皇帝需要讨好SPQR(元老院和罗马人民),而这种讨好在帝国后期变得越来越没有原则、不讲限度。

其实自凯撒-屋大维时代起,罗马帝国就形成了一个潜规则,新皇帝上任,总是给罗马公民加码一次福利,这样才能获得民众的支持,让老百姓都称颂他的功德,罗马皇帝必须靠这种方式维持政权稳定。

最开始,是直接发钱,后来出现了“免费面包”政策、即罗马城内所有贫穷公民都可以得到免费发放的小麦(两千年后的埃及纳赛尔总统听说后,肯定会实名点赞)。

再后来,罗马皇帝上任、结婚、或每逢大型节日,都需要掏钱请人民们免费去斗兽场看竞技表演,在罗马极盛的最佳元首图拉真大帝时代,某些节日期间公民们连逛窑子都是皇帝私人请客。大家过的那是好一个欢快。

但这也产生了一个问题——发这么多福利,钱从哪儿来?尤其是塞维鲁王朝开始后,皇帝不仅要花钱讨好平民,还要花更多的钱讨好禁卫军,这就更让人头痛了。

最开始的时候还好解决,因为像凯撒、图拉真这样的猛人通过外战就能抢来不少,把罗马人民的欢乐建立在别国人民的被洗劫上,不亦乐乎?而像奥古斯都这样的狠人,前期还能搞点把敌对元老宣布成“人民公敌”然后抄家的行动,几个“狗大户”跌倒,也够罗马人民狂欢一阵了。

可到了帝国中后期,罗马对外蛮族也打不动,对内元老们的既得利益也碰不起,皇帝就开始为怎么讨好老百姓犯愁了。

于是我们的老熟人卡拉卡拉同志就想出了那招《安东尼努斯敕令》,以普发公民权的方式,最后讨好一波自己的人民——虽然我上台庆典不大给力,但你们现在都是罗马公民了,该高兴了吧?老少爷们都乐呵乐呵!

可公民权一旦被普发,罗马的财政体系立刻就出了大问题,原本罗马境内的非公民自由人,是要交什一税的,也就是将自己收入的10%拿出来贡献给帝国。

这种征税方式确实有点不公平,以至于崇尚人人平等的西塞罗也觉得不太好意思,辩解说:这个税吧……它其实就是一种保护费嘛!我们罗马人服兵役流血流汗、保你们非公民一方平安,你们多拿点不是应该的吗?

但卡拉卡拉一普发了公民权,什一税这个维持帝国正常运转的柱石顿时就不存在了。皇帝必须从别的地方想法子弄钱,于是低智商皇帝如卡拉卡拉就把手伸向了罗马真正赖以立国的根本——农工商业主们。

公元213年,就在《安东尼努斯敕令》颁布的次年,卡拉卡拉宣布向帝国境内所有工商业主征收“王冠金”,这种临时加派的新税种征收方式很复杂,总之是给帝国境内的生产贸易极大的提高了成本。帝国境内各种巧立名目的增税、加派,就成了后世皇帝们用以搞钱的惯用手段。

罗马皇帝的这种加派,主要动机不是像东方帝国那般是为了满足其个人或权贵的穷奢极欲,而是为了收买罗马城平民、元老和禁卫军的忠诚,但这样反而让增税更加欲壑难填。

而在增税之外,罗马皇帝还想到了另一种更简便的“捞钱”方式——用刻意制造通货膨胀从有产者那里抢夺财富。

罗马帝国流通的货币主要是金银币,上面印有皇帝的头像,是帝国信誉的保证。公元一世纪,暴君尼禄首开了在货币上跟民众斗心眼的先河,把银币的含银量从100%降低到了90%。这个口子一开,此后历代罗马皇帝都会或多或少在这上面做点文章。但到了卡拉卡拉时代,因为财政困难,福利又需要大规模撒币。所以这家伙来了一把大的:把银币含银量从之前的60%一口气下降到了25%。后世的皇帝更狠,罗马银币的含银量最终降到了不足3%。银币里居然没有银,也算是个奇迹。

这样,国家当然可以用有限的银制造更多的银币,像卡拉卡拉这样的傻皇上可能觉得挺好——这下给禁卫军发工资不犯愁了。

但这样一来,最终受损的其实是所有民众,尤其是那些有产者、工商业主们。劣币的大量流通和物价的飞涨,让罗马境内的商贸秩序荡然无存。在帝国后期,由于滥发的货币已经完全失去了给商品标价的功能,罗马商人们甚至不得不恢复以物易物的商贸模式。

可是以物易物是极不方便各地区之间进行贸易流通,建立比较优势的。再后来罗马农工商业主们自己也想明白了,与其这样,咱还不如别做生意,各过各的算了。于是帝国末期,罗马境内各区域都出现自给自足的庄园化趋势,整个地中海贸易圈因为失去了权威货币而崩溃。

这进而让帝国本身的维系,变得勉强而不必要,强盛一时的罗马帝国最终破碎、消融。欧洲回复到了自给自足、以物易物、很多人一辈子没见过钱长啥样的原始时代。

为了滥发福利、讨好民众而肆意增税,为了扩大政府财权而恶意制造通货膨胀。这是导致罗马灭亡的两个教训。

一千多年前,罗马帝国的的税收和福利背离了初衷,最终形成了一个“奖懒罚勤”的奇妙怪圈,拿帝国中最中流砥柱的那批人的膏血,养了一批寄居在罗马寄生虫和吸血鬼。

一千多年后,这个故事也许会在自称“新罗马”的美利坚重演。

这种窘境,让我想起了美国学者麦瑟·奥尔森(Mancur Olson)在《国家的兴衰》一书中提出的观点:历史上任何帝国的衰败,都根源于利益集团固化导致的社会僵化,政府因为失去了有效改革的余地而胡乱施为,最终将国家拖向衰亡。

当年的罗马是如此,如今的拜登政府也如是,由于拜登为击败川普所组成的执政联盟过于庞大,身为“盟主”的拜登不能触动其中任何一方的既得利益。而撒钱、印钞、加税是他为数不多的可控权力,他就把这些都做到了极致。

所以我不同意国内一些推崇拜登的人吹捧“拜登新政”是“罗斯福新政2.0”的观点。罗斯福新政的功过尚且不论,但他改革的顺序是先颁布《国家工业振兴法》等法案治本,再去调整财税政策治标。这跟拜登上台后专注于在撒钱、印钞、加税上使劲,完全是两个路数。

所以,无论你是中国人还是美国人,至少在未来四年里,都不需要过多忧心中美对抗的问题。美国霸权最大的挑战者,不是俄罗斯、不是中国。。。